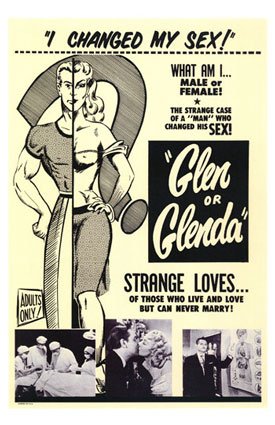

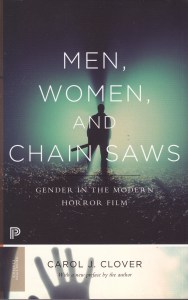

Some thoughts I hope I’m allowed to share on Father’s Day: I recently saw a review of The Wicker Man that pointed out (rightly) that my treatment of gender was outdated. Similarly, the (few) readers of Nightmares with the Bible make a not dissimilar observation about my use of Poe’s formulation of women in danger. I am very much aware that gender studies (which wasn’t even a potential major when I was in college) have done much needed work in clarifying just how complex a phenomenon it is. I have posted several times on this blog about precisely that. Still, we all write from a position. My training is not in horror studies, and it’s not in gender studies. My writing, despite the price, is intended for non-academic readers, but I too may be between categories here. I’m trying to escape the academy that has already exiled me, but the framing of my questions is too academic. I get that.

I also write from the perspective of a man. There’s no denying that I write as a straight, white male. This is how I experience the world. And how I experience horror. Returning to Nightmares, I think my point might’ve been better expressed as noting that writers, directors, producers, and others in the film industry understand that viewers of their particular films may be more moved by a female possession than a male. Or, in Wicker, that publicly expressed concerns about rape and sexual violence are more commonly expressed by women. Statements can always be qualified, but that happens at the expense of readability. There’s no such thing as a free lunch after all.

Academics can’t be blamed for doing what they do. They critique, poke, and probe. My books since Holy Horror have been intended as conversation starters. But they’re conversation starters from the perspective of a man who watches horror and tries to understand why he reacts to it the way he does. There is an incipient ageism, I fear, that sometimes discounts how people raised to use “man” when referring to mixed or indeterminate genders—taught so earnestly by women who were our teachers—sometimes take our earliest learning for granted. Those early lessons are often the most difficult to displace. I try. Really I do. I’ve had over six decades looking at the world through a straight man’s eyes. I welcome comment/conversation from all. Of course, my intended readership has never been reached, and they, perhaps would have fewer concerns about my view. Romance (hardly a feminist-friendly genre), after all, is one of the best selling fiction categories, even today. And many of the writers—generally women—express the gender-expected point of view. That’s a genre, however, outside my (very limited) male gaze.