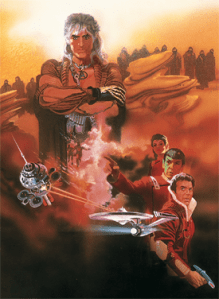

I haven’t seen Noah yet; the timing didn’t work out this past weekend. Besides, you don’t always get to see what you want. Nevertheless, the critics are already having a go at it, and the movie is gathering such attention because it is of biblical proportions. Or more properly, of biblical origins. One commentary in The Guardian suggests that, since knowledge hasn’t moved since Aristotle, that gods really have no place in movies. I have to wonder about that. Sure, the wealthy and powerful seldom have a need for gods, being the captains of their own destinies. Until it comes time to face the flood that all mortals face, and even the rich have to acknowledge that no ark is big enough to take it with them. Who wouldn’t want to have a little divine intervention then? Indeed, God strikes me as the almost perfect antagonist. Before you begin to hurl your stones this direction, think of the book of Job, underrepresented at the box office, but about as honest as they come. We, like Noah, are not in control of this vessel.

To quote Tom Shone, in his review, “[God] has no desire, no needs, no social life, no private life, no self-exploratory intellectual life to speak of.” Of course, the biblical view is quite different. God in the Hebrew Bible is not omnipotent. In fact, he (and he is generally male) comes across as quite lonely. He has anger issues, to be sure, but he is a troubled character rather like a Disney Hercules who doesn’t know how to control his power. Add him to the mix with willful, self-satisfied human beings and it sounds like an afternoon at the movies to me. Perhaps film makers don’t present God with weaknesses—that would be the worst of heresies—but it is also perhaps the most biblical of heresies.

Going back to Aristotle, perhaps it is not that gods should be left out of drama, but that human ideas of God are what writers call a Mary Sue. A Mary Sue is a perfect character with no flaws, the kind of person we first learn to write, since we believe people—and gods—are only good or evil. Then we begin to discover shades of gray. More than just fifty. Characters are complex and experience conflicting wants and wishes. Thus, as Shone notes, God wants people to procreate, but then wants to destroy them. Afterwards he is upset at what he has done. What could be more human than that? The perfect god who knows no struggles, and who never has to fight for what he wants, would be a boring deity indeed. That’s not the divinity skulking around Genesis, however. I’ll have to reserve judgment on Noah’s god until I get to the theater. It seems to me, at this point, that a wee touch of evil makes for deities that are closer to those we experience in our own workaday lives.