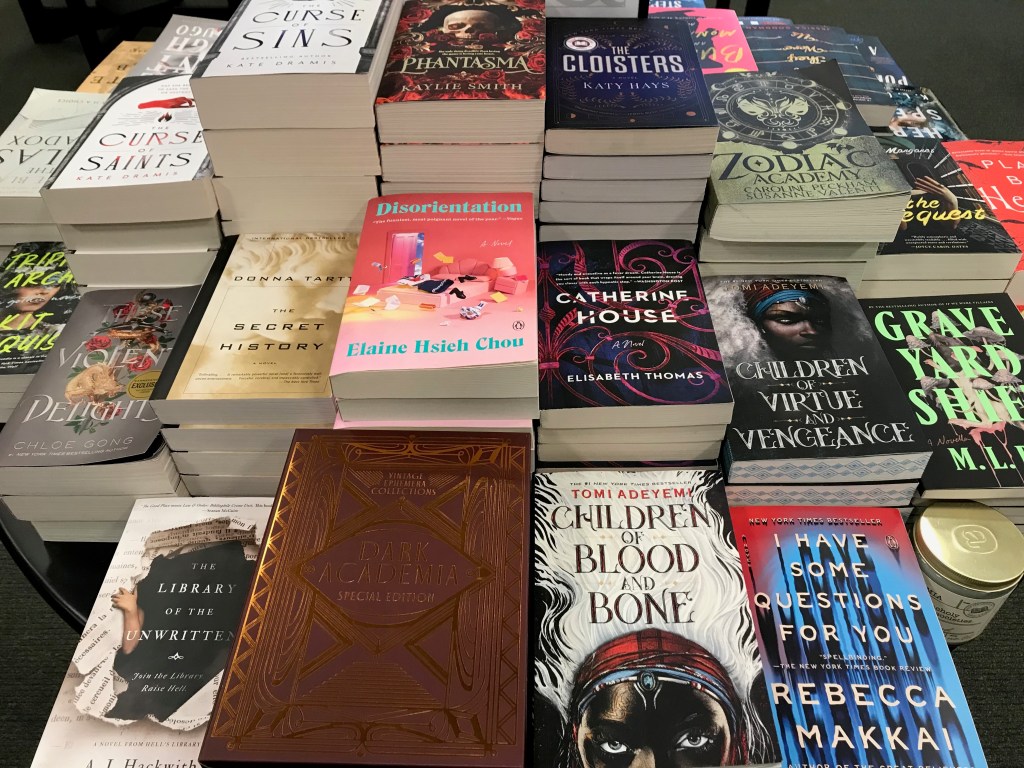

As I attempt to trace the contours of dark academia, I’m learning that much of my reading has been classified that way by others. My main engine for discovering this is Goodreads, making me think I should shelve my own books more. Also, I recently visited a local Barnes and Noble where one of the front tables was dedicated to dark academia. Looking over the titles gave me fiction reading ideas for months. In any case, apart from classical dark academia, where the setting is an institution of higher, or specialized learning, the category for many includes books about books. This would pull in titles such as Carlos Ruiz Zafón’s The Shadow of the Wind, which I read before my current conscious interest in the genre. I think I was looking for gothic books back then. I include, on my personal list, books about students with dark experiences, such as Familiar Spirit by Lisa Tuttle.

The books about books category does shed some insight. I love Italo Calvino’s If on a Winter’s Night a Traveller, but it’s not really dark enough to be, well, dark academia. I understand the critique that dark academia tells stories of privilege, but that dissipates somewhat when including books about books. Higher education is, and remains, a domain of privilege, but it is possible for those raised poor (such as yours truly) to break in. I enjoyed higher education throughout the eighties and into the aughties. After that it began to get far too political and business-oriented. (Not that I wouldn’t go back if I had half a chance. Or even a quarter.) My point is, dark academia can deal with those who lack privilege, but I also believe there’s no point in denying privilege does exist. And opens doors.

Dark academia is new enough that its parameters are permeable. To me the real draw is that a fair bit of sculduggery really does exist in higher education. The reading public seems eager for it. Thinking of all the odd, somewhat tenebrous things that occurred in the course of my couple of decades in academia, the genre rings true to me as well. As I think back over the books I’ve read, I think maybe I should build a shelf especially for dark academia. I’m trying to read in it more intentionally now, but I’ve been unintentionally exploring it for decades. When you add books about books, Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose joins the crowd, and I read that one all the way back in seminary. I tried to be part of academia, but there’s a darkness about an unrequited love, and so it just makes sense to me.