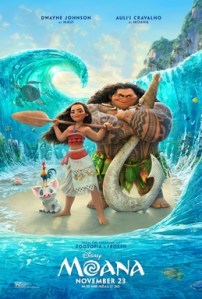

Apropos of both building your own deity and Disney, my family went to see Moana. Now, I have to admit up front to being a bit behind on my Polynesian mythology. Scholars of the history of religions feel terribly insecure if they don’t read the languages or haven’t spent time with the culture first-hand. I’ve seen the Pacific Ocean a few times, but never from the point-of-view of an islander. In fact, one of the areas of growing interest in biblical studies is the interpretation of Holy Writ by islanders. Their perspective, it seems clear, is different from others in more populated land masses. So Moana, which delves into Pacific islander mythology, was a brand new world for me. More than hearing about the demigod Maui, it was a chance to consider what destruction of our ecosystem looks like to those who have more limited resources at hand. Those who, when global warming really kicks in, will be the first to become homeless.

Apropos of both building your own deity and Disney, my family went to see Moana. Now, I have to admit up front to being a bit behind on my Polynesian mythology. Scholars of the history of religions feel terribly insecure if they don’t read the languages or haven’t spent time with the culture first-hand. I’ve seen the Pacific Ocean a few times, but never from the point-of-view of an islander. In fact, one of the areas of growing interest in biblical studies is the interpretation of Holy Writ by islanders. Their perspective, it seems clear, is different from others in more populated land masses. So Moana, which delves into Pacific islander mythology, was a brand new world for me. More than hearing about the demigod Maui, it was a chance to consider what destruction of our ecosystem looks like to those who have more limited resources at hand. Those who, when global warming really kicks in, will be the first to become homeless.

One of the strange things about living in the post-truth world (defined as the world after 11/9) is that many movies, novels, and other creative explorations I encounter seem to underscore the demon we’ve invited in. Moana is about a girl who saves her people, but she only does so by defying the man in power. Had she not journeyed beyond the reef, her people would’ve starved on their island. Meanwhile the big white man prepares to assault the White House and all that our founders held dear: an educated leadership. Progress. Fair treatment for all. Someone needs to remind these short-sighted individuals that every landmass is an island.

As we approach the end of 2016 it’s time to think of where we’ve been. At the theater, an ad by Google showed the newsworthy events of the year. There could not have been a better rendering of the high hopes with which we began and the sorrow with which we’ve come to an end. Our scorn of education has caught up with us and we’ve asked “the man” to please destroy our world and enslave our women and deport anyone who’s different. We need a lesson in how to build better deities. We need to be willing to admit that a girl might know more than her father. We need to learn the wisdom of the islanders.