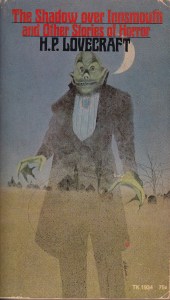

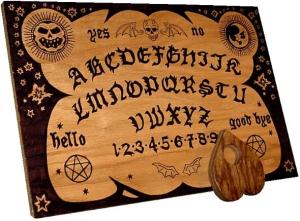

The truth is, only experts and professionals can really keep up with horror films. As the most successful genre of, well, genre films, there are tons of them. I completely missed Ouija when it came out about a decade ago, despite the fact that it did well at the box office. The only reason I watched it now was that a friend sent me a list of horror films from a reputable website that recommended the prequel to Ouija, but I felt that I needed to see the original before finding out what happened behind the scenes. The original didn’t fare well with the critics and it’s pretty clear why. The story, although it has twists, isn’t really convincing and the acting is off at times. (Five teens left alone to watch a haunted house while their parents just take off for weeks at a time?) Still, it’s atmospheric, and it plays on a scary theme.

I must confess that ouija boards frighten me. I consider myself both rational and skeptical (in the classic sense), but there’s just enough doubt with spirit boards. I’ve never owned or played with one. (Interestingly, the movie was funded in part by Hasbro, the current seller of the game.) In fact, when I discovered the Grove City College yearbook was called Ouija, I was a bit put off. (By the time I graduated they’d changed it to The Bridge.) Although GCC wasn’t really traditionally gothic, like most colleges it had its share of ghost stories. Even in conservative Christian country things go bump in the night. And while most stories told about tragedy after using an ouija board are unverified in any way, still…

So, the movie posits a deceiving entity that kills teens who contact it. I suspect I need to watch the prequel to find out why. It does manage to have a few scares, but it’s mostly about atmosphere. I agree with Poe on this point—atmosphere’s often the point of a story. Although the critics are right (who discovers a body in the basement and goes to an asylum for advice instead of notifying the police?), some of us do watch horror films for this kind of haunted house experience. And while I’ve got Poe in the room, the threat to young ladies is there. One thing missing, though, is any talk of religion. No Ed and Lorraine Warren warnings of demons. This is a straight-up nasty dead person who likes to kill those who want to communicate with their dead friends. It does create a mood. And it cries out for a prequel.