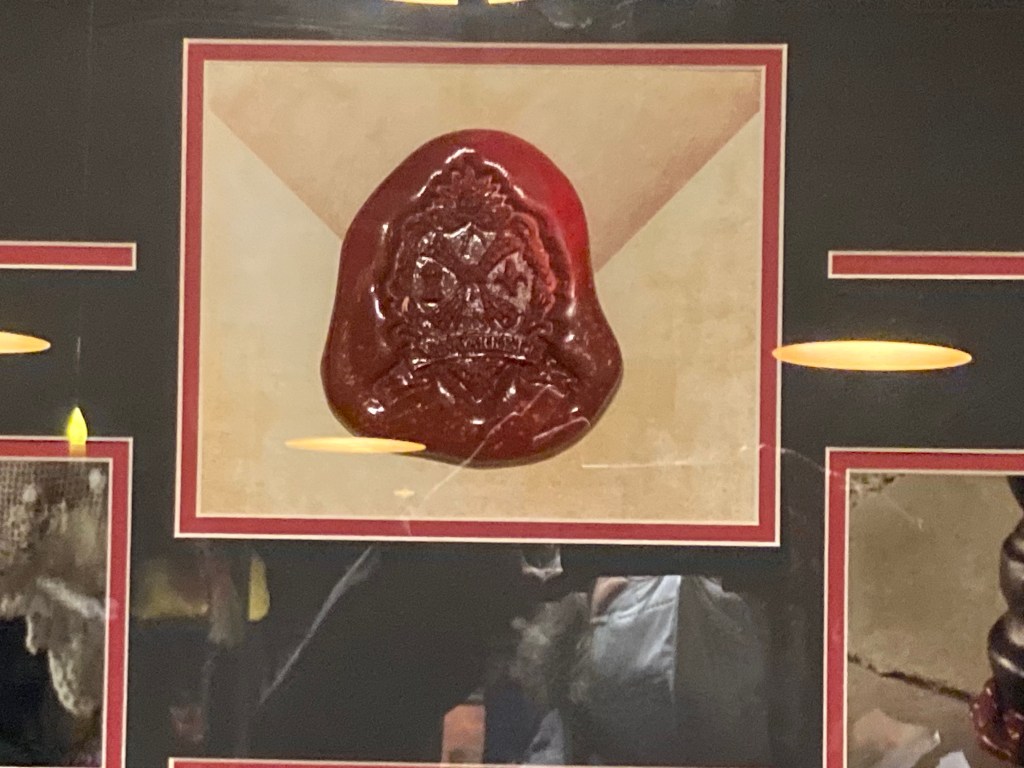

A Nightmare in New Hope is a fairly intimate space. The owner told us that the collection will change and grow, given that he’s still collecting. Having a particular interest in Tim Burton’s Legend of Sleepy Hollow—having a book (ahem) on the subject coming out soon (cough)—I was particularly anxious to see what props they had. To make sense of this it helps to have seen the movie, but you’ll catch on, even if you only know the Disney version of the story. There were three main items from the movie that they have on display. One is the wax seal used for the Van Garrett will, used as the movie opens. The seal is quite large. Of course, movies substitute props from time to time, blended by celluloid magic. CGI doesn’t leave as many tracks.

The second artifact is one that wouldn’t have occurred to me to have even existed. This was the animatronic horse’s head for Daredevil, the Headless Horseman’s mount. There are a couple scenes in the film involving horse acting, and I’d just assumed that trained animals were used. Being up close and personal with this artificial head, a couple thoughts came to mind. One is that right next to it, it’s quite obvious that it’s artificial. The second thought was just how much thought and effort goes into a big-budget movie. For a few seconds of a close-up horse head, this model had to be constructed and used and then set aside. I asked the owner about how such things were acquired, and he noted that production companies don’t keep everything. He also noted that movie artifact prices have skyrocketed. Both because horror is now popular and because CGI, as noted, doesn’t leave tracks.

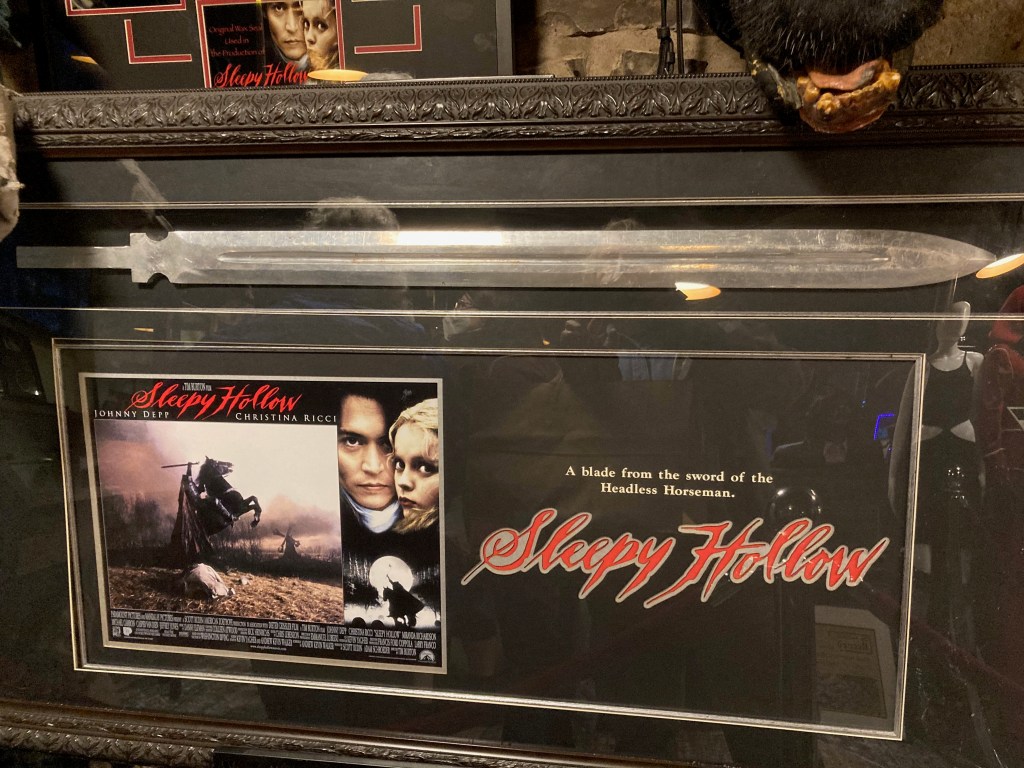

The third, and most proudly displayed Sleepy Hollow piece is the Headless Horseman’s sword. This appears in the movie far more often than either Daredevil’s head or the wax seal. One of the aspects of Washington Irving’s story I discuss in Sleepy Hollow as American Myth is that the Horseman’s weaponry changes over time. I won’t say more since, like museum owners, those who write books hope that they well sell a few copies. I’ll be revisiting A Nightmare in New Hope from time to time. For the items on display, I’d seen probably 90 percent of the movies, and a few of them I’d discussed in some detail in either Holy Horror or Nightmares with the Bible. Of course, the Sleepy Hollow book is forthcoming (ahem).