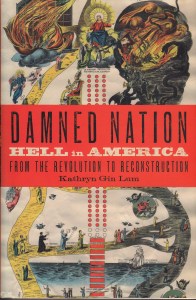

I’d never come across the term “religious melancholics” before, but somehow it seemed to suit me. Perhaps that goes without saying as I’m reading Damned Nation, by Kathryn Gin Lum. While sitting on a bus. We’re sitting in traffic and the guy sitting next to me has obviously just finished a cigarette before climbing aboard. Having grown up as the victim of second-hand smoke for my first two decades in life, I’m thinking about Hell as well as reading about it. You see, Gin Lum’s descriptive subtitle is Hell in America from the Revolution to Reconstruction. The fact that Hell’s alive and well, despite some evangelicals’ attempts at annihilating it, suggests that it’s best to keep informed on the topic. This book’s mostly historical, however, reporting how Americans interpreted Hell in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

I’d never come across the term “religious melancholics” before, but somehow it seemed to suit me. Perhaps that goes without saying as I’m reading Damned Nation, by Kathryn Gin Lum. While sitting on a bus. We’re sitting in traffic and the guy sitting next to me has obviously just finished a cigarette before climbing aboard. Having grown up as the victim of second-hand smoke for my first two decades in life, I’m thinking about Hell as well as reading about it. You see, Gin Lum’s descriptive subtitle is Hell in America from the Revolution to Reconstruction. The fact that Hell’s alive and well, despite some evangelicals’ attempts at annihilating it, suggests that it’s best to keep informed on the topic. This book’s mostly historical, however, reporting how Americans interpreted Hell in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

As with most histories, I find the earliest material the most interesting. Gin Lum tends to focus, naturally, on preachers at this period since they are the ones most likely to talk about eternity. The thing that struck me the most was the number of people she describes who, after contemplating (a primarily Calvinist vision of) Hell, attempted suicide. I tend to think of suicide as a contemporary problem, but obviously it has been a steady human practice since our species first learned that you don’t have to wait for someone else to help you slough off this mortal coil. It is troubling, however, that it was a “doctrine” barely found in the Bible that led people—most of whom later became preachers—to try to kill themselves. It also seemed a touch odd that evangelicals in those earlier days of our nation didn’t find it troubling that those leading the flock had almost sent themselves to perdition. These early days of literal Hell believing were most interesting indeed.

The phrase “religious melancholics” comes from the resistance. There were those—generally skeptics, doctors, psychologists, and the like—who felt that the preaching of hellfire and brimstone took a toll on the healthy psyche, particularly of the young. As one of those who grew up attending revivals where Hell was a featured guest, I know that my life has been a prolonged attempt to avoid said eternal lake of fire. Even when I rationally learned that there is no three-tiered universe in which it still fit, and that the idea was cobbled together from a variety of religions into the ultimate scary place, Hell still manages to haunt me. Does it keep me moral? I don’t suppose that to be the case, since I have tended to believe people are basically good. Don’t bother trying to convince me logically that Hell doesn’t physically exist. I know that already. It’s the mental one that I’m trying to avoid. And that can be a full-time job for a religious melancholic brought up on a diet of overcooked theology.