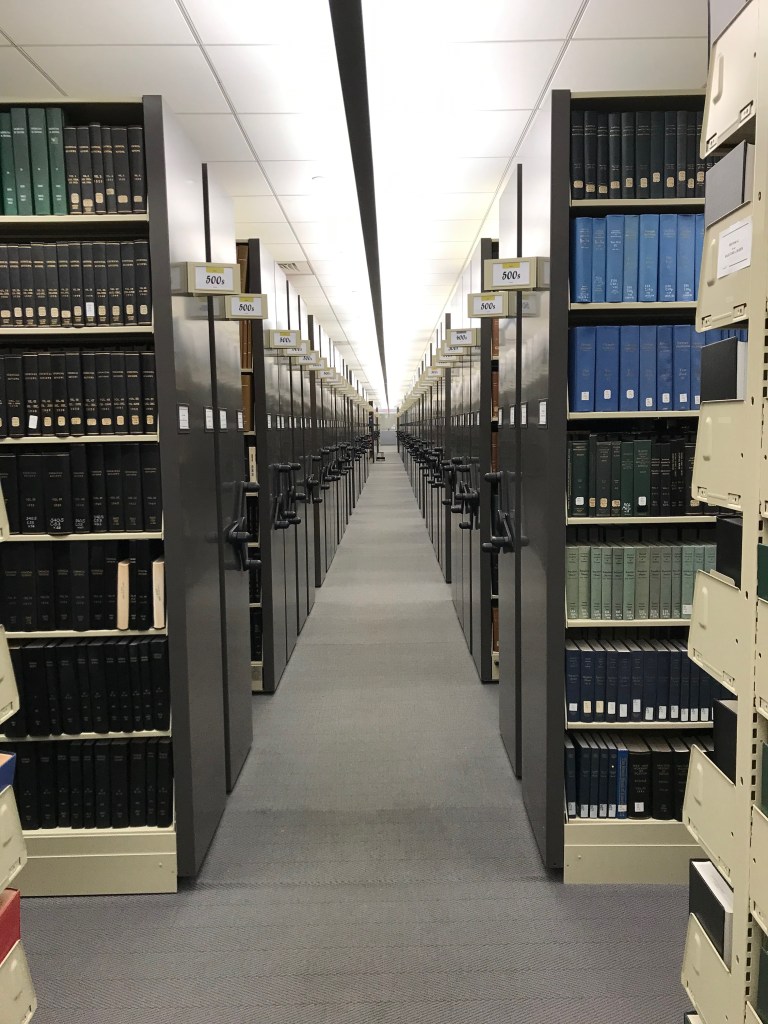

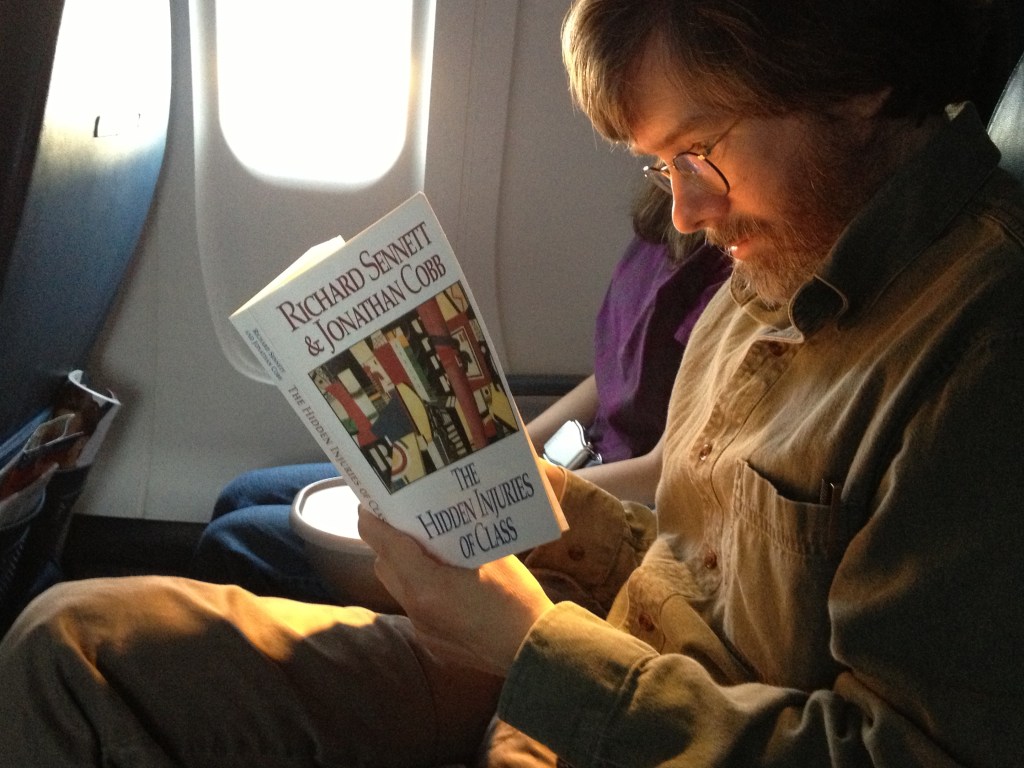

I need to know the origins of things. Call it a sickness if you will, but I’m compelled to trace things to their source. This is why I went on to earn a doctorate, and it’s a trait that hasn’t left, despite my career malfunction. My interest in origins was recently reawakened by the citation, in a book, of a source that was incomplete. I turned to the internet, of course. I found the source, reprinted on a Tumblr page, for which I was grateful, but there was no proper citation there either. Instead, a link to another webpage, which itself consists of yet another link. Even after pages of googling, I was no closer to finding the source. This is why I miss libraries. You were there with books, some of them centuries old, looking at the source. Outside the academy this rarely happens. Particularly when you work 9-2-5.

The internet age is one of taking someone else’s word for it. That’s why it’s important to establish credibility. The website where I found the information—the top ranked site on both Ecosia and Google—had old books as the background, but no “about” page. Who had put this information here and where did s/he get it? The item I was looking for was from the 1700s. I don’t have a print copy lying around and I was wondering what the source was—a book? A journal article? A newspaper? An actual archive? And why can’t Google find it in a library? I know the source actually exists because I also found it referenced in a reputable print book, but one with inadequate citation. Some of us were cut out for this kind of thing. Constitutionally researchers. But you have to work to live.

One of the greatest pieces of advice ever is to stay curious. It helps keep a mind active, even a 9-2-5 one. I’ll keep looking for this mysterious source. I’ll check out likely references in the bibliography. I’m sure that other people have the same compunction not to take someone else’s word for it. Particularly not an anonymous poster on some website. Especially in this day of AI lies. One of my high school teachers once said that a reputation for being trusted is something you earn by lifelong cultivation. If people know you are a reliable source, they will believe the things you say. Anonymous information can be helpful from time to time, but without knowing the source I always remain skeptical. And curious.