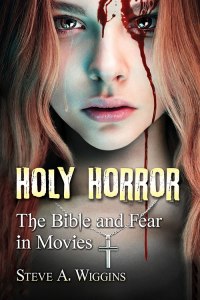

It seems that Holy Horror is now available, although I haven’t seen it yet. According to the McFarland website it’s in stock just in time for the holidays. Those of you who know me (few, admittedly) know that I dabble in other social media. One of my connections on Goodreads (friend requests are welcome) recently noted that he does not like or watch horror. Indeed, many people fall into that category. His follow-up comments, however, led me to a reverie. He mentioned that reading the lives of the saints and martyrs was horrific enough. One of the claims I make in Holy Horror is that Mel Gibson’s Passion of the Christ is a horror film. My friend’s comment about martyrs got me to thinking more about this and my own revisionist history.

Traditionally horror is traced to the gothic novel of the Romantic Period. Late in the eighteenth century authors began to experiment with tales of weirdly horrific events often set in lonely castles and monasteries. From there grew the more conventional horror of vampire and revenant tales up into the modern slasher and splatter genres. I contest, however, that horror goes back much further and that it has its origins in religious writing. Modern historians doubt that the mass martyrdoms of early Christianity were as widespread as reported. Yes, horrible things did happen, but it wasn’t as prevalent as many of us were taught. The stories, nevertheless, were written. Often with gruesome details. The purpose of these stories was roughly the same as the modern horror film—to advocate for what might be called conservative social values. The connection is there, if you can sit through the screening.

Holy Horror focuses on movies from 1960 onward. It isn’t comprehensive, but rather it is exploratory. I’ve read a great number of histories of the horror genre—a new one is on my reading stack even as I type—and few have traced this phenomenon back to its religious roots. Funnily, like horror religion will quickly get you tagged as a weirdo. Perhaps it’s no coincidence that both goths and priests wear black. As I’ve noted before on this blog, Stephen King’s horror novels often involve religious elements. This isn’t something King made up; the connection has been there from the beginning. We may have moved into lives largely insulated from the horrors of the world. Protestants may have taken the corpus from the crucifix for theological reasons, but for those who’ve taken a moment to ponder the implications, what I’m saying should make sense. Holy and horror go severed hand in bloody glove.