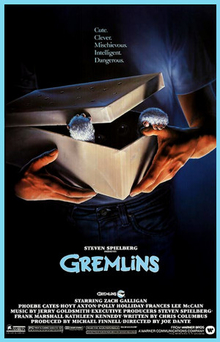

Gremlins holds up pretty well with the years. My renewed interest was sparked by holiday horror—I had last seen the movie in a theater in 1984, when it came out. Having grown used to CGI, I was surprised to re-learn that the gremlins were puppets but that it was so obvious was also a surprise. Although comedy horror, or horror comedy, had been around for years at that point, as critics pointed out, the contrast here was stark. This could be a kid’s movie (and was one of the reasons behind the shortly new PG-13 rating) but the nasty gremlins could be unexpectedly brutal. I’d forgotten that Billy’s mother was so effective—killing a gremlin in a blender and another in a microwave. The story has been retold and/or parodied often enough that a summary isn’t necessary, but given my recent interest in both gremlins and holiday horror, it’s worth a few moments’ reflection.

Holiday horror is more than a scary movie that happens to occur on a holiday. In my definition, the horror has to derive from the holiday itself. In Gremlins the gift of Gizmo is based on the fact that it’s Christmas, otherwise Rand wouldn’t have been looking for a gift for his son, starting the whole chain of events. More than that, the reason I didn’t go back to the movie again in my college and grad school years was the story Kate tells about her father on Christmas. Like some parents, I felt like what was a fun little story was a bit too distressing given the holiday setting. Would the story have worked set at a different time of year—remember, it was released in summer—with the commentary that it makes about consumer culture? No, this had to be a Christmas movie and the fear comes from that fact.

The gremlins are given minimal backstory here, although Murray Futterman tells Billy and Kate that gremlins come from foreign merchandise and they tinker with machines. Gremlins had been used in horror before, and given that the canon of classic movie monsters was being set from the thirties through the fifties (gremlins appeared as monsters as early as the forties) they fit right in. They’re inspired monsters. People naturally feel vulnerable on planes and monsters in the atmosphere can be particularly frightening. And the fact that technology frequently malfunctions, well, wouldn’t it be nice to have a monster to blame? Reading up on the movie made me curious to see the sequel, which, it seems wasn’t too badly received. I’m glad to have used a small portion of the holiday season to have refreshed my memory.