It began as a quest for immortality. Sometimes, however, you don’t recognize something even when it’s all around you. As an historian of religion, the quest for immortality is a familiar one. Certainly the ancient Egyptians believed they had found the keys, at least for royalty, and most religions haven’t given up trying since then. Some clonal plants have achieved extreme longevity. Since they grow by extending their roots, rather than by sexual reproduction, a single plant can remain alive as long at, at least 8,000 years. The specific plant to which I’m referring is the box huckleberry. I first learned to pick huckleberries for food in the Pacific Northwest. In that part of the country, I’ve learned to identify the plant from a distance and have spent many contented hours picking berries. Time, however, is something always endangered for those of us aware of its passing.

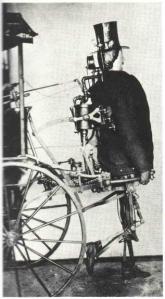

The box huckleberry colony in the Hoverter and Sholl Box Huckleberry Natural Area in Pennsylvania is about 1,300 years old. Summer is waning and my family wanted to see it. Indeed, for this particular colony, development probably destroyed parts of the system and so it has to be preserved. With that strange east-coast worldview, “just over there in Pennsylvania” comes to mean things are closer together in the imagination than they really are. Driving three hours just to see a huckleberry colony became more appealing when we combined it with the idea of visiting the National Watch and Clock Museum in Columbia, Pennsylvania. Both concepts were obviously related to the theme of time. They aren’t quite as close together as they look on a map. Map, after all, we are told, is not territory. The museum exists in a fixed location marked by a street address, so we went there first. There will be plenty to write about that later. As, ironically, we didn’t allow as much time as we should have for the museum, we had to head out further west and north to find the elusive huckleberry. All we had were the GSP coordinates and the name of a local town.

From the length of the line of cars behind me, the locals preferred to travel faster. Knowing only the relative direction and an approximate mile count, we stumbled upon Huckleberry Road and knew we must be close. Off into the woods we drove. As onetime manic geocachers, we had learned to both trust and distrust a GPS, but there was a trail head out here and a single parking spot. No one else was around. The signed indicated we were in the right place, but where were these ancient huckleberries? The ones we generally harvest grow knee-to-waste high with distinctive leaves. We walked the entire nature trail in frustration. How could a 1,300 year-old plant hide so well? Frustrated, we went back to the start. Fortunately, there were brochures. We found the box huckleberries. Indeed, they had been all along the trail, but we didn’t know what we were seeking. Just a few inches high, they cover the ground like a carpet. A few ripe berries poked through. We were in the presence of an entity that was older than Beowulf. Indeed, in the Middle Ages, this plant had been alive. Without the guide we’d never have realized we were standing in the midst of a kind of immortality.