Although the Allegheny Mountains are hardly the Rockies—they’re much older and gentler on the eye—they harbor many tourist locations. Even before my daughter attended Binghamton University, I’d been drawn to the natural beauty of upstate New York. Prior to when college changed everything, we used to take two family car trips a year, predictably on Memorial and Labor day weekends, when the weather wasn’t extreme and you had a day off work to put on a few miles. One year we decided to go to Sam’s Point Preserve (actually part of Minnewaska State Park) near Cragsmoor, New York. It features panoramic views, a few ice caves, and, as we learned, huckleberries. What my innocent family didn’t suspect is that I’d been inspired to this location suggestion by the proximity of Pine Bush.

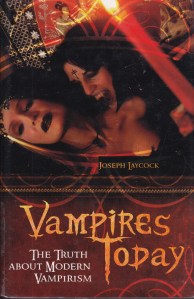

A friend just pointed me to an article on Smithsonian.com by my colleague Joseph Laycock. Titled “A Search for Mysteries and Monsters in Small Town America,” Laycock’s article discusses how monster pilgrimages share features with nascent religion. People report strange encounters with all kinds of creatures and objects, and science routinely dismisses them. Odd encounters, however, leave lasting impressions—you probably remember the weird things that have happened to you better than the ordinary—and many towns establish festivals or businesses associated with these paranormal events. Laycock has a solid record of publishing academic books on such things and this article was a fun and thoughtful piece. But what has it to do with Pine Bush?

Although it’s now been removed from the town’s Wikipedia page, in the mid 1980s through the ‘90s Pine Bush was one of the UFO hot spots of America. Almost nightly sightings were recorded, and the paranormal pilgrims grew so intense that local police began enforcing parking violations on rural roads where people had come to see something extraordinary. By the time we got to Pine Bush, however, the phenomena had faded. There was still a UFO café, but no sign of the pilgrims. I can’t stay up too late any more, so if something flew overhead that night, I wasn’t awake to see it. Like Dr. Laycock, I travel to such places with a sense of wonder. I may not see anything, but something strange passed this way and I want to be where it happened. This is the dynamic of pilgrimage. Nearly all religions recognize the validity of the practice. It has long been my contention, frequently spelled out on this blog, that monsters are religious creatures. They bring the supernatural back to a dull, capitalist, materialistic world. And for that we should be grateful. Even if it’s a little strange.