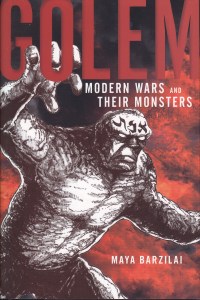

Investigating a new field, at least on an academic level, involves a little disorientation. Part of this derives from the fact that academics didn’t use to write about monsters. Another part of it, however, is that those who do such writing have been doing so while my attention was elsewhere. It’s not easy to learn dead languages reasonably well. I didn’t pay much mind to the golem, being as it is, a “modern” monster. Probably responding to early modern pogroms, the golem was considered a defender of persecuted Jews. He was, however, a mindless defender. Made of animated clay, the golem was brought to life by magic and could only be killed in the same kind. Maya Barzilai has written a masterful account of how this monster relates to war. Golem: Modern Wars and Their Monsters explores how modern golem stories (and there are many) tend to relate to situations of conflict.

Investigating a new field, at least on an academic level, involves a little disorientation. Part of this derives from the fact that academics didn’t use to write about monsters. Another part of it, however, is that those who do such writing have been doing so while my attention was elsewhere. It’s not easy to learn dead languages reasonably well. I didn’t pay much mind to the golem, being as it is, a “modern” monster. Probably responding to early modern pogroms, the golem was considered a defender of persecuted Jews. He was, however, a mindless defender. Made of animated clay, the golem was brought to life by magic and could only be killed in the same kind. Maya Barzilai has written a masterful account of how this monster relates to war. Golem: Modern Wars and Their Monsters explores how modern golem stories (and there are many) tend to relate to situations of conflict.

I had read about the golem before, and had trouble locating many academic resources on the creature. Barzilai demonstrates how much there is to ponder. It seemed, prior to reading her book, that the golem was mostly obscure, but it turns out that many writers, artists, and filmmakers have appropriated the clay giant over the years. Those who trace the history of comic books suggest that Superman was originally a kind of golem figure. I hadn’t realized that the golem had his own short-lived comic book series. When a people are persecuted repeatedly, having a secret weapon may not seem a bad thing. But the golem is difficult to control. It rampages. It can kill the innocent. Barzilai raises the question of whether a people with an unstoppable weapon are ever justified in using violence.

That question hangs pregnantly over the present day. The rich white men that run this country feel that they’ve been oppressed. Not willing to admit that it’s morally reprehensible to treat women as objects (they’re “hosts,” we’re told), blacks as inferiors, or hispanics as illegal, they bluster away about family values that aren’t consistent with anything other than threatening those who are “different” into submission. And yes, the Jews are among those these white men scorn. I wonder where the golems have gone. It could be that, like those of us self-identified as pacifists, that those who know how to make golems simply can’t justify violence. Barzilai didn’t intend for this in her book, I’m sure. Still, each new era brings new perspectives to these monsters made of clay.