Weekends, it seems, are incomplete without being among books. You might think that someone who works in publishing might want to get away from books in the off hours, but quite the contrary. I love a good walk in the woods in autumn. Especially if it’s followed by a trip to the local independent bookstore. It just feels right being among books. I realize that I’m in the minority by expressing such an opinion, and that the book buying (and book publishing industry) is (are) small compared to other forms of passing one’s time, but they are significant beyond their size. My wife and I have scoped out the various indie book sellers all around. When we have to take the car in for service, we drop it off, have lunch at a diner, and stroll down to the bookshop. It’s a pleasant way to spend an afternoon.

Here’s the sign on our Clinton indie. In case you can’t make it out, the legend says “This is a book shop. Cross-roads of civilization. Refuge of all the arts. Against the ravages of time. Armoury of fearless truth. Against whispering rumour. Incessant trumpet of trade. From this place words may fly abroad not to perish as digital waves but fixed in time. Not corrupted by the hurrying hand but verified in truth. Friend, you stand on sacred ground. This is a book shop.” I especially appreciate the sentiment of sacred ground. Indeed, sanctuaries of all sorts often house books. As libraries experience funding difficulties, civilizations are in the throes of collapse. Just to have books around me makes me feel secure.

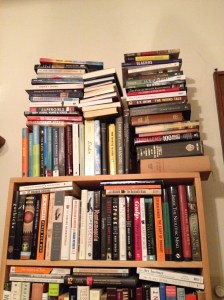

Some months ago we had to have a refrigerator replaced. Our apartment has a strange, offset back door that makes getting anything of size in or out difficult. The front door is a fairly straight shot, but just beyond the entryway I had set up a bookshelf after we moved in. The appliance guys came in, jaws literally dropping. “I’ve never seen so many books in one place,” one of them said. They then complained and told me they couldn’t get the old fridge out as the landlord had said they’d be able too. “Your books are in the way,” they complained with accusatory tones. I had to unload the books from two shelves and move them while they watched. I, the lover of books, was duly chastened. I’m afraid my love affair with reading has only become more passionate since that day. The books are back on their shelves and they’ve been joined by more friends. What is a weekend without books but a wasted opportunity?