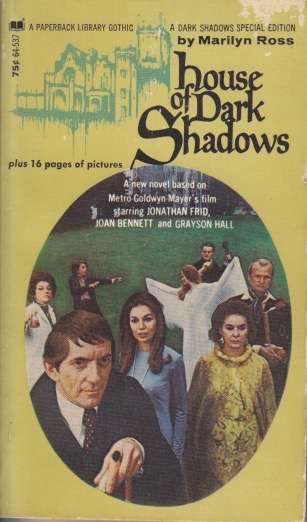

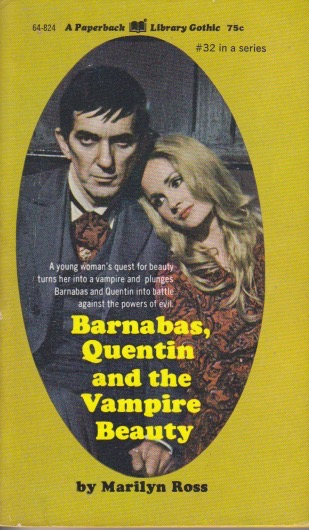

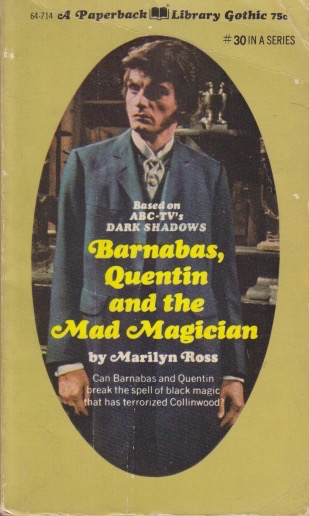

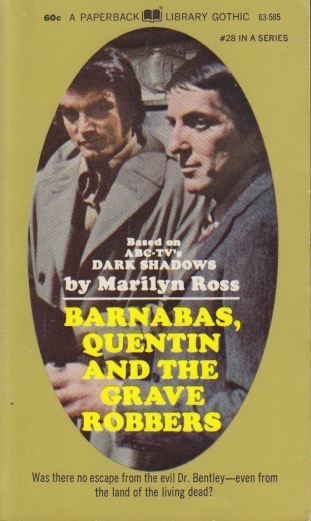

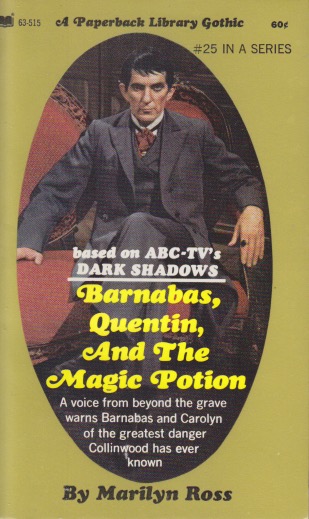

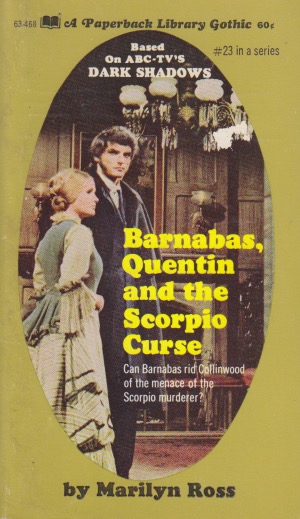

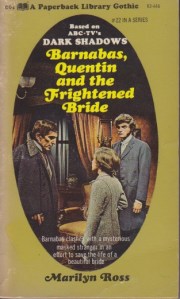

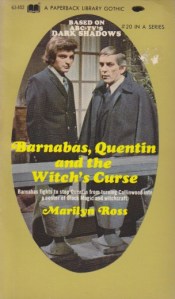

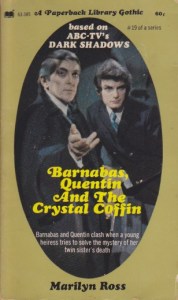

Nostalgia is a funny thing. Although it can strike at any age, somehow after the half-century mark it’s particularly easy to get swept into it. As I written about many, many times, I was drawn into the Marilyn Ross Dark Shadows novels as a tween. In my mid-to-late forties, when the internet made it possible, I started to collect all the volumes from 1 through 32. It took several years. I had to find them via BookFinder.com and our level of income didn’t support buying more than one every few months. Then in 2022, having difficulty locating the last of the original series, I found a seller on eBay offering up the whole set. The price for that set was less than the least expensive final volume I could find. I did what any nostalgic guy would do.

We don’t really buy antiques, but I’d been looking for an office desk (this was before the scam). I’d been using a craft table for a desk for years and it seemed that I really needed something with a better organizational range. This led me to stop into a local antique shop. They ended up not having much furniture, but they did have aisles of nostalgia. A few weeks later when it was too hot and humid to be outdoors, I revisited the shop. This time, relieved of the burden of seeking a desk, I was able to browse at leisure. It’s like going to a museum but not having to pay admission. I turned a corner and I saw something I’d never seen before. A collection of Marilyn Ross Dark Shadows books.

It wasn’t a full set, but I had, prior to finishing my own collection, never seen more than one or two together in any single place. As a child I’d buy them at Goodwill. As an adult, on BookFinder. All those years in-between, I always looked for them when visiting used bookstores. I visit said shops whenever possible. In decades of looking I’d only found one in the wild once or twice, and always by its lonesome. This was a completely new experience for me. It was also quite odd to be seeing them and not having any need to buy them. I have a full set. The nostalgia was almost overpowering. I couldn’t help but think of how even a few years ago I’d been pawing through to see if there were any I hadn’t yet found. All for reliving a bit of my childhood.