I think I’ve discussed memory before. I forget. Anyway, I recently ran across Ebbinghaus’ Forgetting Curve. Now, I’ve long known that when you reach my age (let’s just say closer to a century than to 1), your short-term memory tends to suffer. I value my memories, so I try to refresh what’s important frequently. In any case, Ebbinghaus’ curve isn’t, as far as I can tell, age specific. It’s primarily an adult problem, but it also resonates with any of us who had to study hard to recall things in school. The forgetting curve suggests that within one hour of learning new information, 42% is forgotten. Within 24 hours, 67% is gone. This is why teachers “drill” students. Hopefully you’ll remember things like the multiplication table until well into retirement age because you had to repeat it until it stuck. Where you put the car keys, however, is in that 42%.

I’m a creature of habit. One of the reasons is that I fear forgetting where something important might be. The other day it was my wallet. In these remote working days you don’t need to put on fully equipped pants every day. Pajama bottoms work fine for Zoom meetings and if you don’t have to go anywhere, why fuss with the wallet, cell phone, pocket tissues-laden pants? You can put your phone on the desk next to a box of tissues. The wallet gets left in its usual pocket. One day I pulled on the pants I last wore and as I was headed to the car noticed my wallet was gone. Fighting Ebbinghaus, I tried to remember where I’d last used my wallet. We’d gone to a restaurant the previous weekend that seemed the most likely culprit. It could’ve fallen out in the car, or maybe down a crack in an overstuffed chair. I couldn’t find it anywhere, swearing to myself I was going to buy one of those wallet chains if I ever found it again.

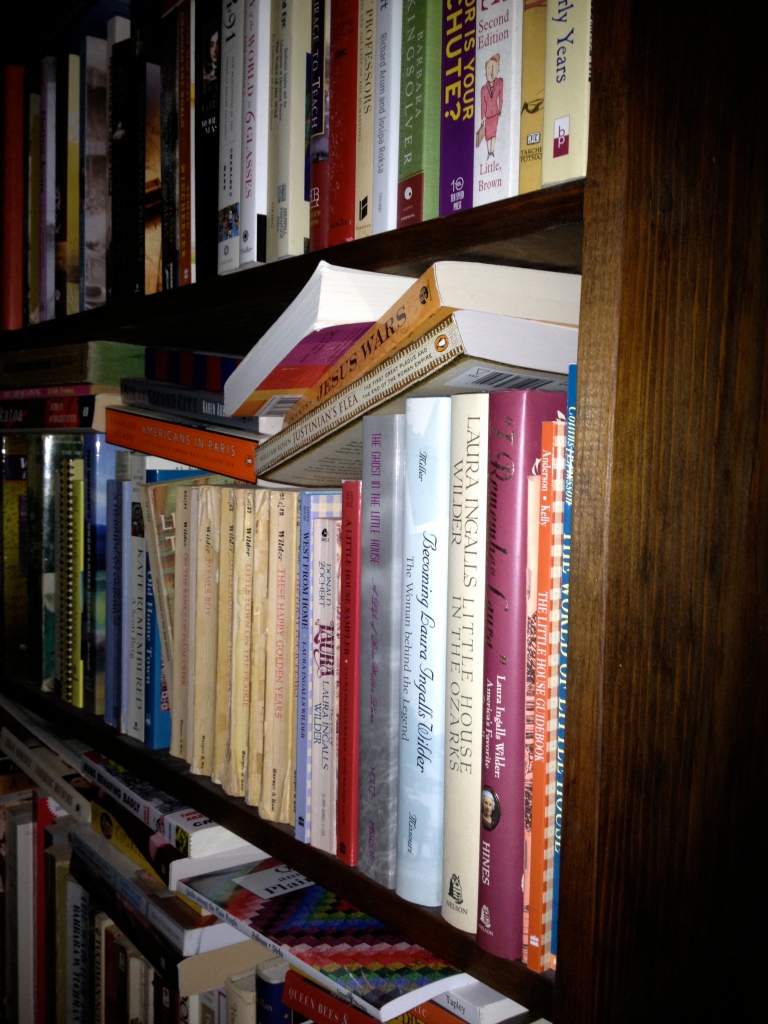

(I did eventually find it, in the bathroom. Apparently this has happened to others as well.) In this instance, my memory was not to blame. It had been right in the pocket where I last remembered putting it. But other things do slip. Think about the most recent book you read. How much of it do you remember? That’s the part that scares me. I spend lots of time reading, and more than half is gone a day after it’s read. Unless it’s reinforced. The solution, I guess, is to read even more. Maybe about Ebbinghaus’ Forgetting Curve.