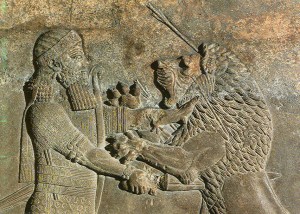

Irony comes in all shapes and sizes. Over the past several decades various fundamentalist groups have built replicas of what they believe to be life-size versions of Noah’s ark. All of these are approximations because the cubit was never an exact measure. Nobody knows what gopher wood was. Most of them ignore the fact that the story of Noah clearly borrows from the more ancient Mesopotamian flood story where the measurements of the ark differ. In any case, these arks—some containing dinosaurs and others not—are made for convincing people that Genesis is to be taken as history. While there is some irony in that itself, the larger irony comes in the various proofs that are given that such things really would work to preserve all species since evolution could not have happened. To work such models have to be seaworthy.

One such ark, according to the BBC, has been detained in Ipswich because it is unseaworthy. An ark may be useful on dry land for drawing tourists, but would such a large boat work on the open ocean? All of this brought to mind a Sun Pictures documentary from my younger days. Giving the ark a makeover, various literalists re conceived the classic design from children’s Bibles to a more boxy, sturdy shape. This was based on alleged encounters with the ark on Mt. Ararat. To test this new design, the producers made a scale model and tested it in a pool of water and declared it eminently seaworthy. Of course, there’s no way to make water molecules shrink to scale to test whether a full-sized ark could actually handle the stresses and strains of a world-wide flood.

Ship building is an ancient art. Peoples such as the Phoenicians, the neighbors of ancient Israel, achieved some remarkable feats in ocean travel without the benefits of modern technology. They didn’t have boats large enough to hold every species of animal that exists today, but they sure knew how to get around. The real issue with literalism is the failure to recognize ancient stories for what they were—stories. Such tales were told to make a point and the point was often obvious. The obsession with history is a modern one—indeed, the ancients had no concept of history that matches what our current view is. Borrowing and adapting a story was standard practice in those days. Unaware that centuries later some religions would take their words as divine, they told stories that, in the round, just wouldn’t float.