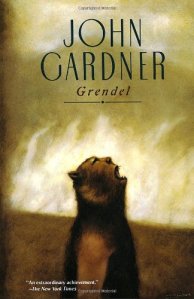

Sometimes I think that if I had to do it all over again, I might’ve chosen Beowulf instead of the Bible. Let me define “it” here: if I had to pick a vocation that would lead to personal fulfillment and personal penury, that is. Beowulf is the earliest written story in English and, it’s a monster story. What’s not to like? In honor of Banned Book Week, I decided retroactively to read a banned title, John Gardner’s Grendel. An early parallel novel narrated from Grendel’s point of view, we are introduced to the introspective, existentialist monster who is really just wondering, like the rest of us, what the point of it all is. Not surprisingly, the protagonist often addresses the question of religion—indeed, it might even be at the heart of the story.

Sometimes I think that if I had to do it all over again, I might’ve chosen Beowulf instead of the Bible. Let me define “it” here: if I had to pick a vocation that would lead to personal fulfillment and personal penury, that is. Beowulf is the earliest written story in English and, it’s a monster story. What’s not to like? In honor of Banned Book Week, I decided retroactively to read a banned title, John Gardner’s Grendel. An early parallel novel narrated from Grendel’s point of view, we are introduced to the introspective, existentialist monster who is really just wondering, like the rest of us, what the point of it all is. Not surprisingly, the protagonist often addresses the question of religion—indeed, it might even be at the heart of the story.

In chapter nine, Grendel sits in the darkness in the ring of wooden gods of the Danes when Ork, the great, blind priest stumbles in and believes the monster is the Destroyer god. As Grendel toys with his theology, the old priest understands this all as a revelation, and although Grendel gives him no answers, the words are taken as divine utterances. The other priests, finding their leader out on a winter’s night, insist that he has gone senile, that gods do not reveal themselves like that. The old man, however, is unshakeable in his faith. As in much of the novel, there is more going on here than meets the eye. The deluded priest believes a monster is his god.

The question of theodicy (literally, the judging, or justification of God) is never-ending for theists. The world is a problematic place (made so, I must note, by human consciousness) for the creation of an omnipotent deity who is good. Too much suffering, Grendel, too many failed expectations. Clergy and theologians have, for centuries, tried to frame a convincing answer to the dilemma. The tack they all studiously avoid is that God is a monster, although some posit that as a straw hypothesis quickly to be knocked down. Gardner, although not a theologian, was the son of a lay preacher and farmer. One suspects that elements of that childhood crawled out through the pond with Grendel. One of the truly tragic characters, a “son of Cain,” Grendel still has an immense power on the imagination. And that power, at times, might even appear godlike.