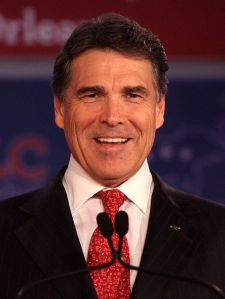

Am I the only one who finds it disturbing that Neo-Con politicians are naïve enough to believe that prayer will solve all our problems? Where was God during the Bush years, for crying out loud? And yet headline after headline speculates about Texas Governor Rick Perry’s prayer-fest scheduled for Saturday. What is more disturbing than the lack of imagination on the part of would-be candidates is the sheep-like following on the part of a large segment of the electorate. If God is going to step in and take charge, he had a great chance back on May 21 and refused to pick up the option. If God was behind politics, why did George W. Bush fail to find Osama Bin Laden? If God is running things, why are so many unemployed? Ah, but the religious pundits have a pat answer: America is a sinful nation. What it takes is religion, Texas-style.

In the many years I spent at Nashotah House, the majority of our students hailed from Texas. They represented the conservative hard-line and doctrinal strappadoes that caused much suffering but still somehow didn’t placate an angry God. That, of course, says more about Nashotah House than it does about Texas. Perhaps it is the logical evolution of a country that began with prominent ministers gleefully describing sinners in the hands of an angry God. Nearly three centuries later and we are being told God is still angry. Thou shalt not hold a grudge, eh? The problem seems less about sinful folks just trying to get by (a la Bon Jovi) than about politicians using their religion to get elected. Centuries down the road it will be the topic of some new series of History’s Mysteries that an affluent, educated, and generally forward-looking nation cluttered its governing bodies with politicians who believed the answer to complex problems is to bow their heads and tell God how to fix it. Are we really half-way there, or have we spread our arms to embrace Jonathan Edwards once again?

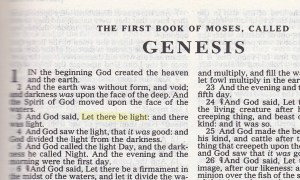

In MSNBC’s article on Rick Perry’s prayer day, it is noted that the book of Joel is cited as an inspiration for the event. For such a brief book, Joel has been at the forefront of a ton of damage wrought by prooftexters. Joel wrote three brief chapters about a locust infestation for which the suggested response was prayer. One wonders if Rick Perry simply prays when the termites begin to gnaw on his expensive home, or does he call Ortho instead? Joel was truly old school. The locusts in his day meant literal mass-starvation. No chemical romance to solve the problem there. Unfortunately we don’t know how that one turned out—Joel doesn’t say. I’m just glad that Governor Perry hadn’t been reading Psalm 137 when inspiration struck, and can I get an amen from the pro-lifers on that?

P.S. Matthew 6.5.