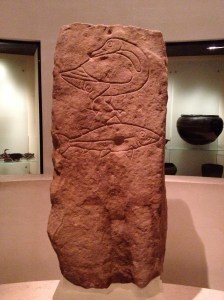

Some people are impulse buyers. In fact, retailers count on it. All those last-minute items next to the cash register while you wait your turn to consume—they beckon the unwary. I have to admit to being an impulse book buyer. I have to keep it under control, of course, since books are “durable goods” and last more than a single lifetime, with any luck at all. A few years ago I was in the shop of the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh. It was my last day in the city where I’d spent my post-graduate years and I didn’t know when I’d ever be back. What could help me remember this visit? A book, of course. Why I chose Monsters, by Christopher Dell, to mark this particular occasion, I don’t know. I love monsters, yes, but why here? Why now? Why in the last hours I had in my favorite European city? It was a heavy book, hardcover and unyielding in my luggage. I had to have it.

Some people are impulse buyers. In fact, retailers count on it. All those last-minute items next to the cash register while you wait your turn to consume—they beckon the unwary. I have to admit to being an impulse book buyer. I have to keep it under control, of course, since books are “durable goods” and last more than a single lifetime, with any luck at all. A few years ago I was in the shop of the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh. It was my last day in the city where I’d spent my post-graduate years and I didn’t know when I’d ever be back. What could help me remember this visit? A book, of course. Why I chose Monsters, by Christopher Dell, to mark this particular occasion, I don’t know. I love monsters, yes, but why here? Why now? Why in the last hours I had in my favorite European city? It was a heavy book, hardcover and unyielding in my luggage. I had to have it.

More of an extended essay than a narrative book, Dell’s Monsters begins with a premise that I never tire of contemplating: religions give us our monsters. At least historically, they have. There is an element of the divine as well as the diabolical in the world of monsters. As a student of art, what Dell has put together in this book is a full-color unlikely bestiary. These are the creatures that have haunted our imaginations since people began to draw, and probably before. One exception I would take to Dell’s narrative is that the Bible does have its share of monsters. He mentions Leviathan, Behemoth, and the beast of Revelation, but the Bible is populated with the bizarre and weird. Nebuchadnezzar becomes a monster. Demons caper through the New Testament. The Bible opens with a talking serpent. These may not be the monsters of a robust Medieval imagination, but they are strange creatures in their own rights. We have ghosts as well, and people rising from the dead. Monsters and religion are, it seems, very well acquainted.

The illustrations, of course, are what bring Dell’s book to market. Many classic and, in some cases, relatively unknown creatures populate his pages. They won’t keep you awake at night, for we have grown accustomed to a scientific world where monsters have been banished forever. And yet, we turn to books like Monsters to meet a need that persists into this technological age. About to get on a plane for vacation, I know I will be groped and prodded by a government that wants to know every detail of my body. Sometimes I’ll be forced into the private screening room for more intimate encounters. And for all this I know that William Shatner was on a plane at 20,000 feet when he saw a gremlin on the wing. Like our religions, our monsters never leave us. No matter how bright technology may make our lights.