I don’t mean to be insensitive. Sometimes I get so busy that I don’t even look at the date for days at a time. This can’t be good, but I was surprised when the anniversary of 9/11 caught me completely unawares this year. That’s the kind of summer it’s been. Not acknowledging 9/11 to New Yorkers is like making ethnic jokes—it’s inherently offensive. The City is always subdued on this date of infamy. Coming the same week as Labor Day this year, I think my timing was just off. In my family, September was always the month of birthdays. My present to my brother of the 12th was late in 2001. I wanted to find something old. Something solid. Something time-honored. I wanted a sense of stability to return to a chaotic world. Being an inveterate fossil collector, I went to a local rock shop and bought him a fossilized cepholapod shell. It wasn’t much, but it was a message and a metaphor.

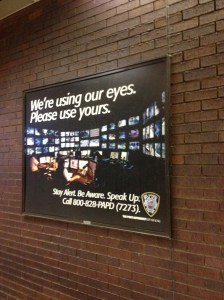

Today, being a birthday and a day after, feels a little like an apology to me. At the time of 9/11 I knew a few colleagues teaching in New York, but in 2001 I’d not really known the city. I’d visited a few times. I was still employed, although my personal career trauma was, unknown to me, already underway. And looking at the state of the world some fourteen years later, I wonder how much better things are. We haven’t suddenly improved, and as a nation we seem more deeply divided than ever. Candidates who resemble their caractitures more than actual people frighten me. The rhetoric is a sermon of doom. Have we all forgotten how that morning felt?

Television reception was poor, or it may have been the tears falling from my eyes as I watched, at the safe distance of Wisconsin. We’d just sent our daughter off on the school bus and now wanted her back home. I called my brother in Pittsburgh in a panic. The news had said a plane had crashed in southern Pennsylvania somewhere. It seemed the the possibilities of horror were endless that day. And yet. I awoke yesterday fretting over work. My mourning routine was harried and frantic. I didn’t even know what day it was. I glanced a paper headline on the way to work and realized that I’d overslept a tragedy. Some scars never heal. Those wounds cut by religion are the deepest. So we find ourselves on the nexus of a tragedy, a birthday, and a new year. How we respond is entirely up to us.