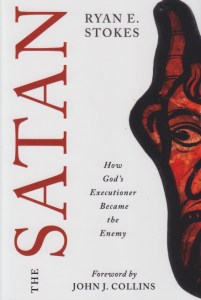

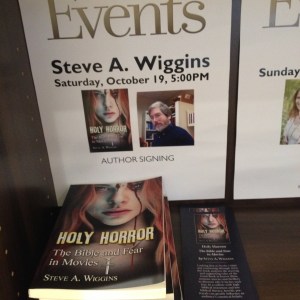

The project that ultimately led to Holy Horror and Nightmares with the Bible was an article. Intrigued that the quasi-horror Fox series Sleepy Hollow was so solidly based on the “iconic Bible” in its first season, I wrote an article on how the Bible functioned in it. After that was published I realized that there was plenty of material for a book on how the Good Book appears in horror films. That book, of course, appeared late in 2018. Nightmares with the Bible was a kind of sequel, but moving in a different direction. It looks specifically at how ideas about biblical monsters (demons) are mediated through horror films. This post isn’t all an introspective about past projects; in fact, it’s about present watching.

At one point in my research I noted that the X-Files wasn’t as biblically based as Sleepy Hollow. I stand by that assertion, but my wife and I’ve been rewatching the X-Files on weekends for several months now. Nearing the end of season two I’ve noticed just how often the Bible appears in it. Unlike Sleepy Hollow, where the entire story was premised on (largely) the book of Revelation, the X-Files has multiple episodes that focus on religion. What we might call New Religious Movements feature in some of the vignettes while others posit older, hidden religions. The Good Book appears visually many times, or, and it’s often quoted, even if not shown. Although some of the episodes are lighthearted, many of them are played as straight horror and address the question of the reality of evil. I hadn’t been alerted by Sleepy Hollow the first time we made our way through the X-Files, but if I had more time, and if anyone were still interested, there’s a book in this.

At one point in my research I noted that the X-Files wasn’t as biblically based as Sleepy Hollow. I stand by that assertion, but my wife and I’ve been rewatching the X-Files on weekends for several months now. Nearing the end of season two I’ve noticed just how often the Bible appears in it. Unlike Sleepy Hollow, where the entire story was premised on (largely) the book of Revelation, the X-Files has multiple episodes that focus on religion. What we might call New Religious Movements feature in some of the vignettes while others posit older, hidden religions. The Good Book appears visually many times, or, and it’s often quoted, even if not shown. Although some of the episodes are lighthearted, many of them are played as straight horror and address the question of the reality of evil. I hadn’t been alerted by Sleepy Hollow the first time we made our way through the X-Files, but if I had more time, and if anyone were still interested, there’s a book in this.

Ironically, even in the light of a political party that takes its energy from a religious base, universities are no longer interested in the study of the subject. I have no reason to believe that these two television series are isolated instances that I’ve just stumbled across. American culture is biblically based, no matter how secular it may be. To my way of thinking, when something like the Good Book has such a strong influence, the response of the rational should be to try to understand it. I know what biblical scholars do all day; I used to be one. Only in recent years have some of them begun to turn toward the concept of the iconic Bible and to consider how it influences American thinking. I can only do this on a small scale, in my free time. What I see, however, like a good X-File, defies explanation.