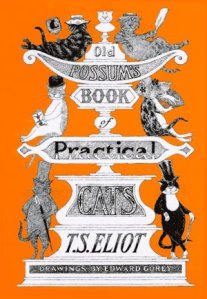

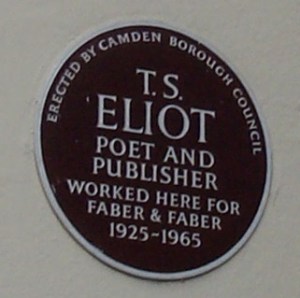

A warm and wet holiday weekend is a good time to watch movies. Since my daily work schedule leave scant time to view anything from most Monday-to-Fridays (and it would claim even more if I’d let it), relaxing often involves watching. I first saw Cats as an ambitious stage production for a local outdoor theater some years ago. Andrew Lloyd Webber has acute talent when it comes to mixing show tunes and popular music; so much so that even a vague storyline will do to carry a show. Cats, of course, is based on a set of children’s poems by T. S. Eliot—Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats. There is no narrative, and they show’s emotionally charged hit “Memory” had to be culled from among Eliot’s other poems. Nevertheless, the musical, now long off-Broadway, exists in a film version that is heavily endowed with religious themes. This weekend I watched it for the n-th time, and each viewing brings out new nuances.

The “story,” such as it is, has two very basic events: Jellicle Cats choose who can be reborn on the night of the Jellicle Ball, and Old Deuteronomy, the patriarch of Jellicles, is kidnapped (cat-napped?) and must be recovered before the choice can be made. The vignettes feature cats dealing with loss, love, and crime. The character who resonates with many viewers is Grizabella, the glamour cat. She is the has-been who sings “Memory,” the cat who was somebody before her fame and fortune faded to a tawdry existence among questionable society. The musical is about transformation, however. Transformation is a religious theme, the desire we have to be something more than we are, to transcend the hand life has dealt us. Now, I’m no theater or film critic, but I have to wonder whether the obvious fades and duets of “Memory” point to Grizabella as the older but sadder version of the young and lively Jemima.

Certainly as the finale builds, Grizabella is chosen to be reborn and is sent to the Heaviside Layer, but the camera keeps coming back to Jemima. She is often framed in the center and the suggestion is made that the new life has already begun. Religion thrives on transformation. I suppose that is the reason I find it so ironic that in politics religion, Christianity in particular, is championed as the pillar of the status quo. Whether they are new or old, religions serve no purpose if they do not challenge the “business as usual” model of the secular world. Perhaps that’s why successful artists such as Andrew Lloyd Webber thrive—they can pack theaters of seekers weekend after weekend, even for decades sometimes. Even those of us watching on the television at home click the eject button with a sense of hope that seems possible only on a holiday weekend.