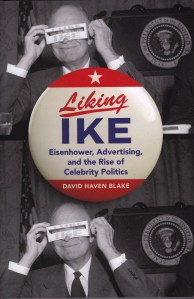

“Television today plays too great a part in our national life for us to allow it to fall into misuse by unprincipled hucksters. We must demonstrate at the polls tomorrow that we will not be treated like suckers at a nation-wide Republican carnival.” The words aren’t mine. Nor are they of this decade. Orson Welles (not the actual source) was reputedly speaking for Adlai Stevenson in the 1956 campaign against Dwight D. Eisenhower. There is a larger context, of course. That context, with a changed cast of characters, reaches right up to this minute and is explored in David Haven Blake’s Liking Ike: Eisenhower, Advertising, and the Rise of Celebrity Politics. In the 1950s Eisenhower disliked and distrusted television as a serious political tool. As Blake traces the story, however, his televised likability led to key components in the elections of John F. Kennedy and the once Democratic Ronald Reagan. Americans, swept off their feet by media advertising, ceased to elect the better candidate, starting over half a century ago.

“Television today plays too great a part in our national life for us to allow it to fall into misuse by unprincipled hucksters. We must demonstrate at the polls tomorrow that we will not be treated like suckers at a nation-wide Republican carnival.” The words aren’t mine. Nor are they of this decade. Orson Welles (not the actual source) was reputedly speaking for Adlai Stevenson in the 1956 campaign against Dwight D. Eisenhower. There is a larger context, of course. That context, with a changed cast of characters, reaches right up to this minute and is explored in David Haven Blake’s Liking Ike: Eisenhower, Advertising, and the Rise of Celebrity Politics. In the 1950s Eisenhower disliked and distrusted television as a serious political tool. As Blake traces the story, however, his televised likability led to key components in the elections of John F. Kennedy and the once Democratic Ronald Reagan. Americans, swept off their feet by media advertising, ceased to elect the better candidate, starting over half a century ago.

Don’t get me wrong—Blake is no conspiracy theorist. His book was published before the otherwise inexplicable election of Donald Trump. It is a disturbing thesis to contemplate. The progression is impossible to miss. Eisenhower permitted Madison Avenue ad men to commodify him, reluctantly. John F. Kennedy embraced the media. He was, however, a career politician. Richard M. Nixon tried to play the game, and did so sufficiently to win. Meanwhile, Ronald Reagan, a Democrat inebriated by the money and power of big business, was a B-movie actor cum politician. He won elections like any high school popularity contest. The course was laid. Elections would be won or lost on superficial appeal. No longer would education, intelligence, and the good of the nation be primary in the minds of the electorate. We would vote the way the media decided we would vote.

Blake’s book, as stated, was written before Trump. Many noted last year, although the media was against him, it handed him the election. Front and center in headline after headline, in retrospect how could the election have gone otherwise? His narrow victory (and downright landslide loss in the popular vote) required every bit of energy on the side of reason to combat. Reason, however, is hardly a worthy opponent to media. We want an entertainer, not a leader. After all, that’s what television’s for. Even now the Tweeting’s on the wall. We mainline our news and wonder why things are the way they are.