It’s funny returning to a city you once felt you knew well. Cities are constantly evolving creatures and even though I got around Boston as a student and then as an employee of Ritz Camera, there were places I simply never found. There was no internet in those days so we relied a lot on word of mouth. If others weren’t talking about it, I’d never hear. I first realized Boston had a Chinatown when attending my first AAR/SBL here. That was in the day when you had to mail or fax hotel registrations in, if I recall, and I do remember staying up to midnight to try to get first choice after that. Ironically, this year I again ended up in that neighborhood, south of the modestly-sized Chinatown. I really didn’t mind, though, since the hotel isn’t too far from Edgar Allan Poe.

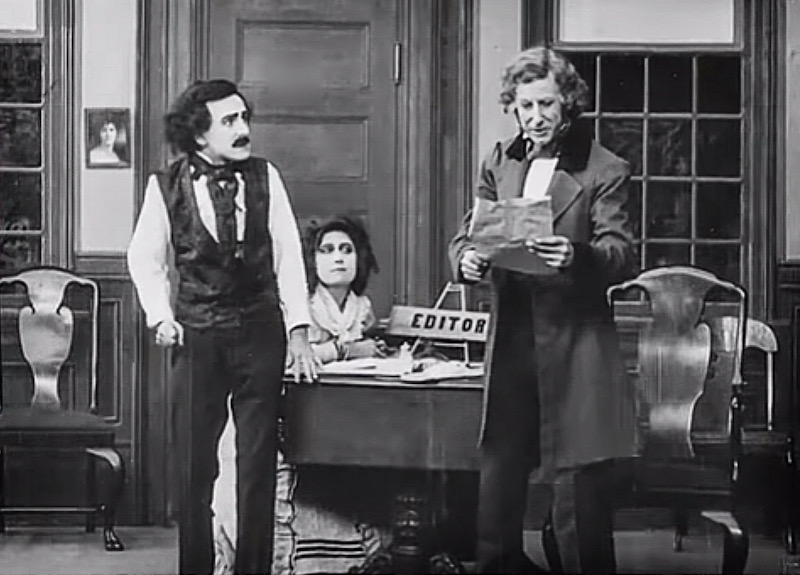

I first learned about “Poe Returning to Boston” from my daughter. She saw it while visiting Boston with a friend. I learned more about it by reading J. W. Ocker’s Poe-Land. When I lived here, from 1985 through 1988, I knew of no public markers of Poe’s presence. None of the more prominent ones were here then. On a trip to Boston for Routledge I sought out the Poe birthplace plaque—the actual house had been torn down—and found it. It’s still here as I saw last night. But the place that was formerly marked only by a painted electrical box now has a statue. Poe, preceded by his raven, walks across the area named for him with a suitcase in hand. Behind him, pages from his manuscripts lie on the ground.

It’s long been known that Boston and Poe had an ambivalent relationship. Poe was born here and lived here for a time, but never felt that the city accepted him. He lived in New York City, Philadelphia, and Baltimore for some time, but mostly considered Richmond, Virginia home. That’s where the Allans lived and where his mother is buried. Poe himself famously and mysteriously died in Baltimore. He had some measure of fame at the time but still lived in poverty. The feeling seems to be that Poe would’ve liked to have liked Boston—it has been my favorite major US city ever since I first moved here four decades ago. Now, of course, I only get back on occasion, mostly when AAR/SBL comes to town. Although Poe wasn’t here the last time I was, I always find something new when I return.