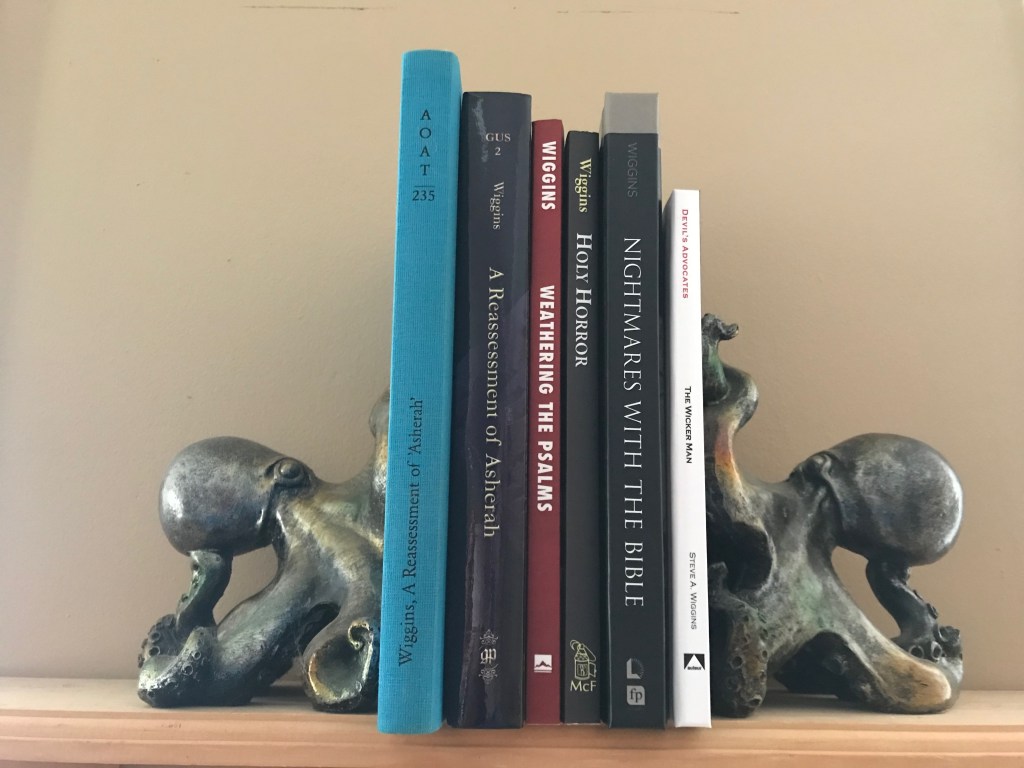

Publish or perish has been around for quite a while and I feel for younger scholars who are trying to publish their collected essays as their second book. Collected essays, in case you’re not familiar with dark academia, are generally what senior scholars do before they retire and they can’t be bothered to rewrite everything into a proper book. Or maybe the topics are disparate and don’t easily fit together in one category. When I was teaching the general rule was an article a year and a second book for tenure. I was able to do this without a sabbatical, and with a heavy teaching load and administrative duties at Nashotah House. It’s a lot of work. My biggest challenge was coming up with ideas for new books. Eventually I published my collected essays on Asherah in the second edition of my dissertation.

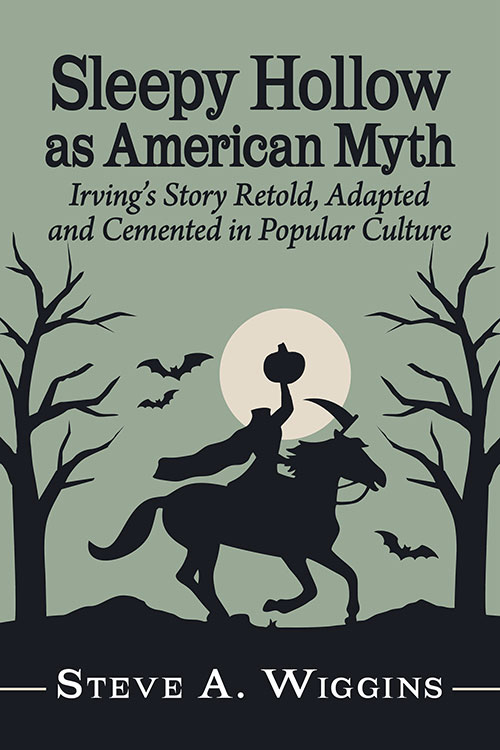

I’d written a 50-page article on Shapshu, the Ugaritic sun deity, that was intended to be my second book. Then J. C. L. Gibson retired and I had to have something for his Festschrift. There it went. It was about that time that I started Weathering the Psalms. That was my “tenure book.” There was over a decade between that and Holy Horror, for a number of reasons. The main one was that I was trying to cobble together a career between Gorgias Press and moonlighting as an adjunct at Rutgers University. There was no time for research and publication. Ironically, that only came after I gave up academia to enter the commercial world of publishing. I see younger scholars now expected to produce that second book, and some of them go for the collected essays approach. I understand.

Back when I was applying for first jobs—and the scene was already very tight, I assure you, despite promises just a few years earlier—I applied for everything. One search committee chair wrote a scolding letter saying I wasn’t senior enough to apply. By the end of his dressing down, he concluded with something along the lines of “unless you’re applying because there are so few positions, in which case it’s understandable.” He was right. So few jobs and so much student debt! I landed at Nashotah and began cranking out the articles. In a moment of weakness I offered to write some further academic treatments after my horror movie books appeared. They don’t do anything for my career, of course. And they take away time from popular writing practice. Who knows? Maybe some day I’ll gather them into a book. Then again, maybe I’ll find myself growing younger too.