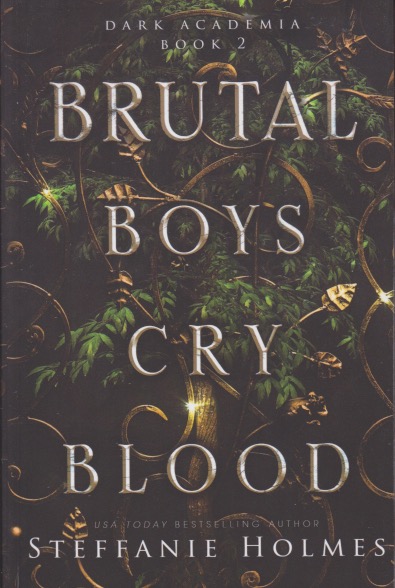

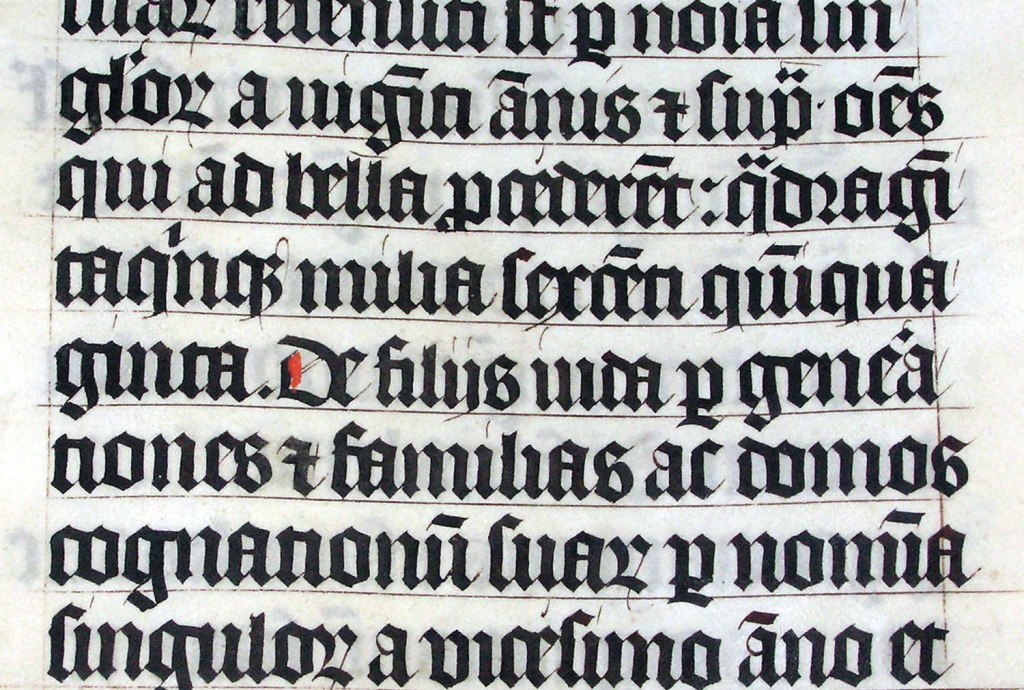

For many years I’ve celebrated Banned Books Week by reading a banned book. What with Republicans wanting only white, hetero, history-denying titles approved, I’m pretty sure that most books I read are banned somewhere. Banned books, of course, see sales bumps and benefit the publisher and author. So instead of reading a noted banned book, this year I’ll hang out my shingle here with but shallow hopes that it will be read. I’m pretty sure, any agents out there, that at least one of my novels would be a banned book. Maybe all of them. You see, in my fiction I’m not the mild-mannered, inoffensive person who blogs here everyday for free. There’s a reason that I keep my pen name secret. I’m pretty sure that most people who know me would be surprised, if not shocked, by what appears in my fiction.

Writing, you see, is where we express the ideas in our heads. I may seem to yak about everything on this blog, but in reality, I’m quite guarded. Many of the horror movies I discuss, for instance, have ideas or scenes that I simply leave unaddressed. I’m trying not to offend anyone here. (A friend of mine who does publish fiction mentioned recently that a significant other in her family suggested that her writing wasn’t controversial enough to be picked up by publishers. I think there could be something to that.) While my mother was alive, I took special care that she wouldn’t discover any of my fiction. Now that she’s gone these two years, I still protect her name with my own nom de guerre. I really don’t want to hurt anybody. I do, however, need to express myself.

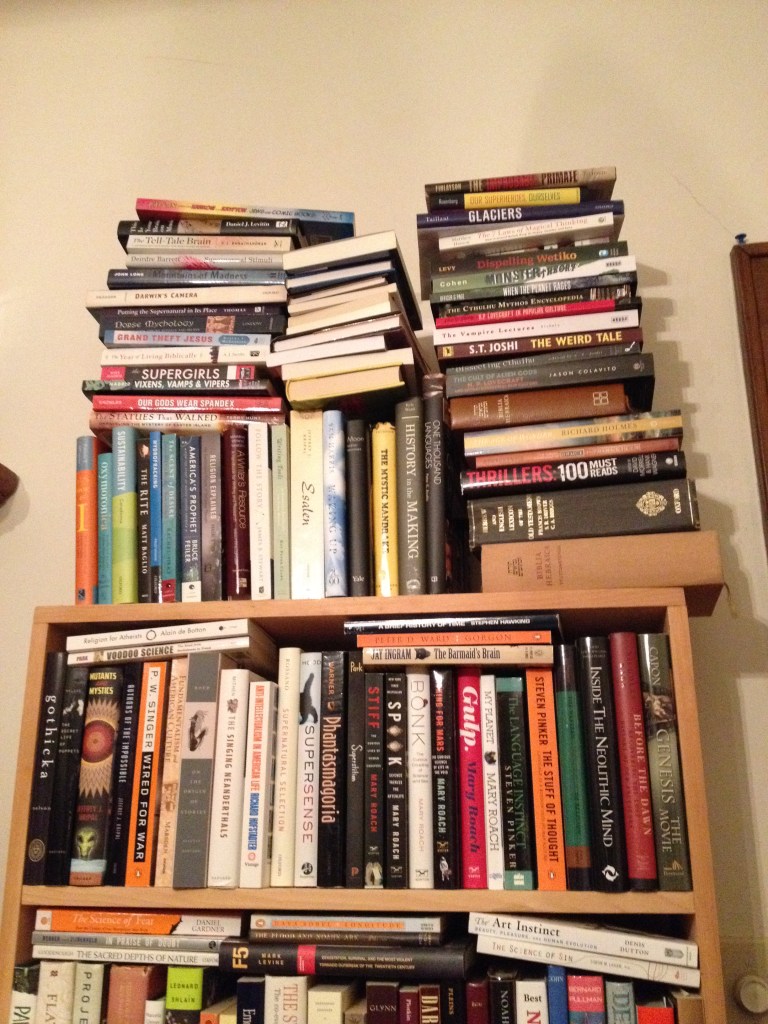

Some of my fiction is horror. Some is just plain weird. The novels are well written, I think, and I’m open to editing. (Agents, I am an editor—I know how this game works!) As long as we’re stuck in a morass of banning books, why not look at a writer who’s more controversial than you might believe? I’ve been writing daily for going on half-a-century now. Think about that. Think about the sheer number of controversial thoughts one might have in that amount of time! Add graphomania to the recipe, with just a squeeze of talent and you’ve got banned books to last a lifetime! I’m not sure any of the books I’m currently reading (five actively, at this point) formally appear on a banned list. But if you want to find one that almost certainly will be, well, my shingle’s out there if you care to take a look.