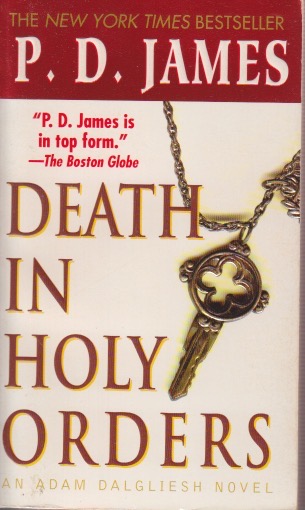

Among the first books I read that might be considered Dark Academia was P. D. James’ Death in Holy Orders. That was so long ago that I don’t remember when, although the inscription tells me it was purchased in 2002. There’s no mystery as to why. There was buzz at Nashotah House when the novel came out. It was about a murder at a conservative Anglican seminary with few students. It seemed very much like Nashotah House to some there, so I read it. Now, I’m not a fan of murder-mysteries. I’ve read nothing else P. D. James wrote. I had no idea who Adam Dalgliesh was. The book was a New York Times bestseller. Reviews were mixed, and among fans of Dark Academia it is scarcely noticed. Still, Dark Academia is still in its toddlerhood. Its boundaries aren’t clear and it overlaps with other genres, as most modern genres do. There may be spoilers below.

In a very complex plot (mystery writers like to show off in that way) a rich seminarian at St. Anselm’s, dies by suicide that was strange but not really suspicious. His wealthy stepfather receives an anonymous letter suggesting foul play and super-sleuth Adam Dalgliesh of Scotland Yard is brought in. After the suicide, an old housekeeper dies of an apparent heart attack. But then an Archdeacon is murdered in the chapel (here was the frisson at Nashotah House). Since there were visitors on the isolated campus at the time, and the Archdeacon was not liked by most people there, it becomes a whodunit with conflicting motives, one of which is to see the seminary closed. It owns artifacts worth millions, and, it seems, someone stands to inherit. Dalgliesh and his team pick through all the clues and, of course, figure out the guilty party.

Even at the end the motivation seems odd. There is a kind of Dead Poets Society letter of confession about preserving the arts. The murderer is a professor of Greek. These elements definitely cast the book into the realm of Dark Academia. Still, it’s primarily a detective novel, and I suspect that’s why many fans of Dark Academia haven’t yet come upon it. I do recall, upon first reading it, that it felt real enough. I was living in a setting not unlike that of the novel and small seminaries do have big secrets. This time through I was less impressed. Super-sleuths are just too smart, which means their writers have to be exceptionally clever. The setting suggests something wrong in the educational world, however, and that is true enough.