Dear Google Scholar and ResearchGate,

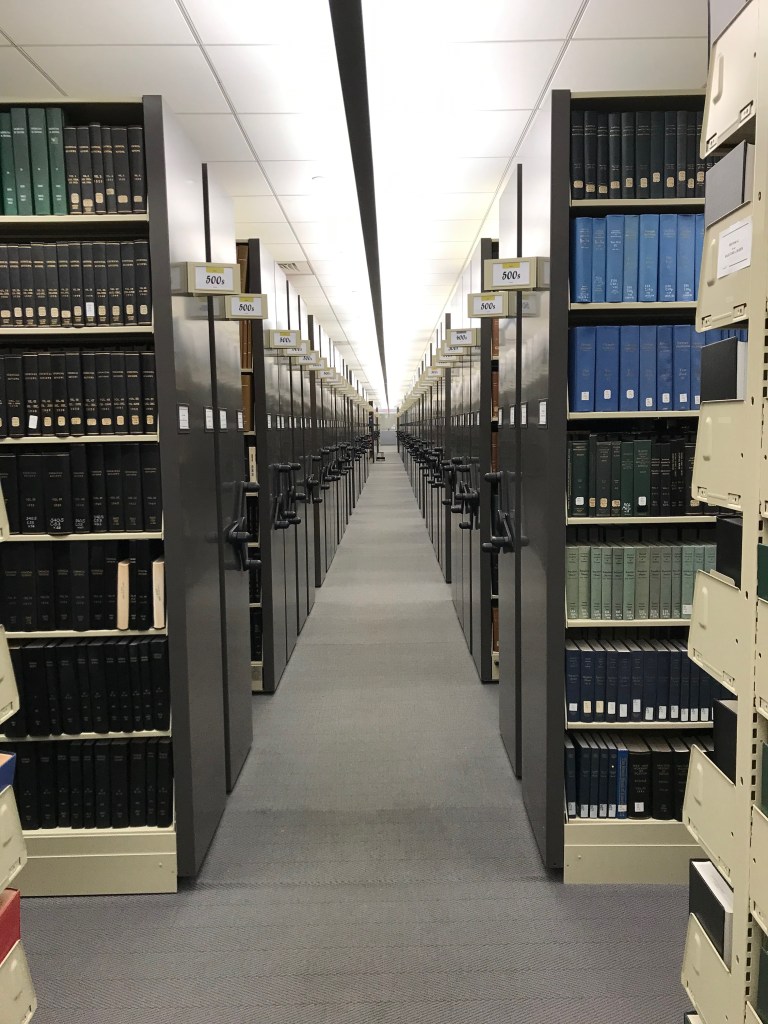

Thank you for listing me as a scholar on your website. I am pleased that my academic publications interest you. I am writing to you today, however, about your verification process. Neither of your sites will verify me since I do not have an email with a .edu domain. Now, I fully realize that even adjunct instructors are often given a university or college email address. This is so students and administrators can reach them. Speaking as a former adjunct instructor at both Rutgers University and Montclair State University, I can verify that such an email address does not verify your scholarship. It is a means of communication only. It does not verify anyone (although it may come in handy if you need to contact someone internally).

For large companies with a great deal of resources, I am surprised at your narrow view of both “scholar” and “verification.” I earned a doctorate at Edinburgh University before email was widely used. I taught, full-time, for over a decade at a seminary that did not request any .edu emails until well into my years there. I taught for a full academic year at the University of Wisconsin Oshkosh. Had you requested “verification” earlier (pardon me, you may not have existed then), I would have been able to contact you from nashotah.edu, uwosh.edu, rutgers.edu, or montclair.edu. Your choice. However, since you only decided to begin your online resources after I had moved into publishing, where the emails end in a .com domain, you were simply too late. The thing about technology is that it has to keep up.

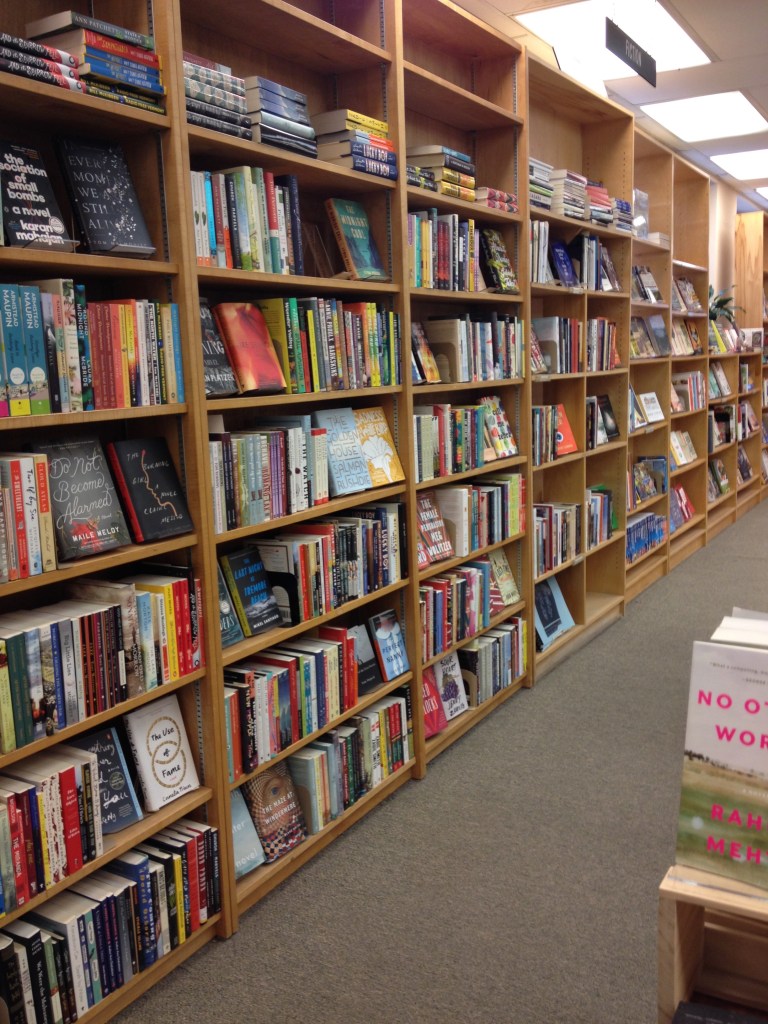

I hardly blame you. My doctoral university was opened in 1583, long before today’s giants were twinkles in the eyes of the likes of Bill Gates or Steve Jobs. Scholars used to write these artifacts, called “books” on paper. They sent them through a service called “the mail” to publishers. I know all of that has changed. The fact is, however, that I have published six scholarly books, and several articles. I am still writing books. I am simply wondering if you can answer the question of when I became unverifiable because of my email address? I have a website that details my educational and professional history. Academia.edu has not asked me to verify myself and my profile there gets a reasonable number of hits. My question is when are you going to catch up with the times? Many, many scholars do not work at .edu-domain institutions. Of course, nobody knows who we are. Thank you for your kind attention.

Unverified