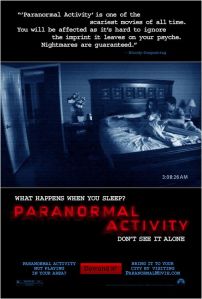

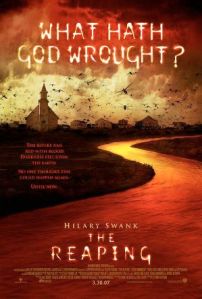

What between Snooki at Rutgers and Mel Gibson’s Passion played at Montclair, I seem surrounded by university controversy lately. A recent article in the New Jersey Jewish News addresses once more the pre-Easter screening of The Passion of the Christ on Montclair State University’s turf. Education is bound to be embroiled in controversy since learning is seldom comfortable. I suspect that is one reason bully governors and the occasional president go after higher education. Few adults like to have their assumptions challenged, their values questioned. I am reminded how blindly many educated clergy accepted the version of the faith story by a disgruntled actor rather than by scholars who actually know what they’re talking about. It is difficult to dismiss the truths of the big screen.

The fact that the wounds opened by this screening are still bleeding weeks after the event demonstrate just how vital open dialogue is. Not only open dialogue, but frank discussion of religion. Many, if not most, religious believers carry on the tradition in which they were raised. Parents begin religious instruction early, and with the threats of a fiery Hell and an enraged divine father overhead, children are shunted toward Heaven everlasting. Not all religions use the same stick and carrot, but no matter what the bludgeon or the vegetable, religions give the faithful reasons to stay in line. Best not to discuss it too much, otherwise doubts might creep in. Educating students in religion is controversial, but necessary as long as people continue in practicing it.

As the article notes, the objection to the film revolved around the fact that no educational component was included. This was one of those “think with your guts” kind of moments, as if feeling sorry for the fictional portrayal of Jesus might somehow make one a better Christian. Educational institutions are duty-bound to teach critical thought when it comes to matters of belief. Emotion is a fantastic motivator, but as history has repeatedly demonstrated, it tends to act without thought. Universities should be open to such constructive criticism, although, it is doubtful that many minds are likely to be changed when the draw at the box office is too great to ignore.