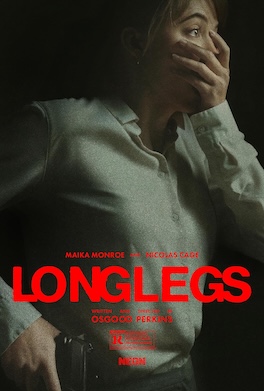

It made a bit of a splash when it came out, Longlegs did. It took a while to get to a streaming service I can access, but I can say that it’s a movie with considerable thought behind it. And religion through and through it. I would’ve been able to have used it in Holy Horror, and it is one of the very few movies where a character corrects another, saying “Revelations” is singular, not plural. Somebody did their homework. Although the plot revolves around Satanism, you won’t be spoon-fed anything. The connection’s not entirely clear, but it does seem to involve some form of possession. The plot involves ESP and a literal deal with the Devil. Things start off with a future FBI agent encountering Longlegs just before her ninth birthday.

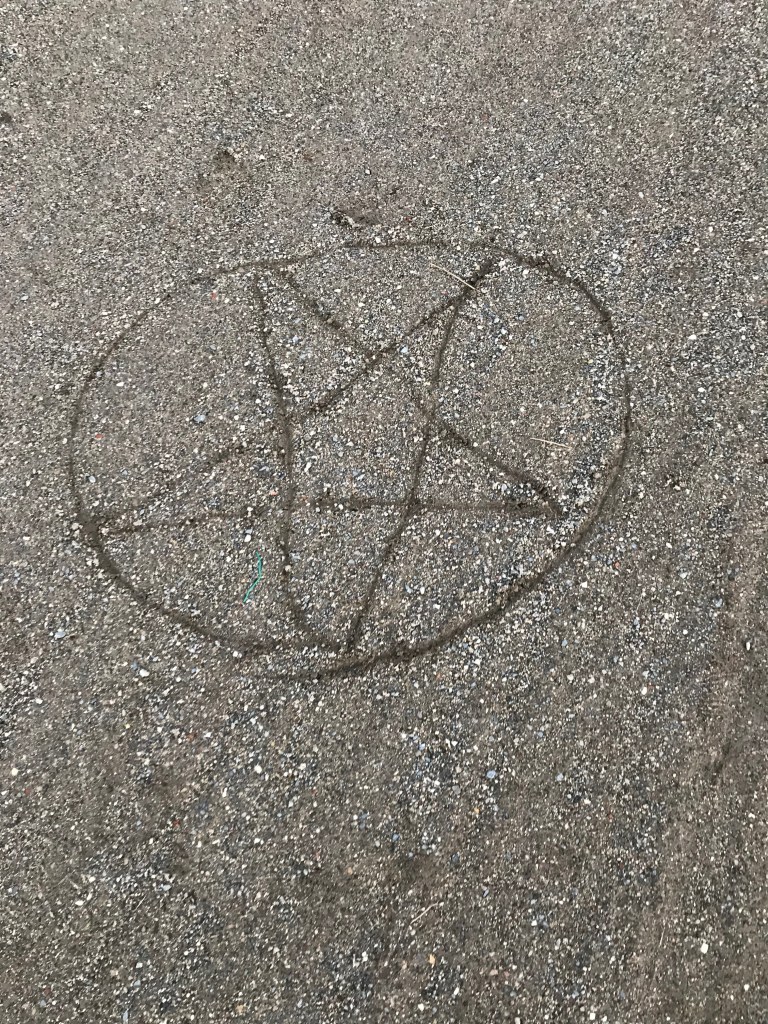

As an adult, she’s forgotten the childhood encounter but a set of murders with a similar MO indicates that a serial killer, called Longlegs, is on the loose. The murders are all inside jobs, and it turns out that a doll with some kind of possessing ability is responsible for inspiring fathers to murder their families. No details of the connection between the dolls, Satan, and the reason for the killings ever emerges. The movie unnerves by its consistent mood of threat and menace. Satan, the guy “downstairs,” appears more properly to be chaos rather than a kind of literal Devil. Satanic symbols are used and there are plenty of triple sixes throughout. The Bible has a role in breaking the killer’s code, but talk of prayer and protection also find their way in the dialogue. Longlegs uses a ruse of a church to get the dolls into his victims’ houses.

I’ll need to see it again to try to piece more of the story together, but Longlegs is another example of religion-based horror tout court. Serial killers are scary enough on their own, but when their motivation is religious they become even more so. Nicholas Cage plays Longlegs in a convincingly disturbing way, but there’s definitely some diegetic supernatural goings on here. The art-house trappings make the plot a little difficult to follow, particularly early on. Religion, however, shines through clearly. The FBI agent, although psychic, has ceased believing in religion while trusting the supernatural. Even as the credits rolled I had the feeling that I’d missed some important clues. And those clues would be important, particularly if I ever do decide to write a follow-up to Holy Horror.