The Orkney Library and Archive was one of my first followers on Bluesky. (I tend to follow back.) I’m not sure why they followed me, but I am grateful. I’m grateful to all followers on social media. Or at least those that aren’t out to scam or stalk me. In any case, seeing the Orkney Library posts always takes me back to the two vacations I took to the Orkneys and I thought it’d be nice to plug a little tourism with personal recollections.

Photo by Maxwell Andrews on Unsplash

My wife and I lived in Scotland for a little over three years. As grad students we didn’t have a lot of money, but we did have the presence of mind to realize that as we got older and settled into family and career that just picking up and going somewhere would become more complicated. I’ve also been a firm believer that travel is a form of education and that people who go places learn by doing so. Hopefully they learn to accept difference rather than to fear it. In any case, after my wife began to work and figure out the British tax system, we found out we had enough money to go somewhere exotic. The Orkney Islands.

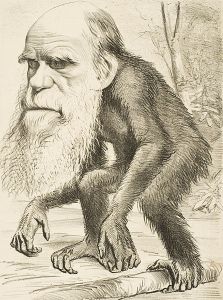

The Orkneys are the antiquities-rich, once Viking-inhabited islands north of mainland Scotland. You can either fly or take a ferry to get there. Since we’d had a small windfall, we flew. That was a mistake, given my history with small planes, but I recovered once we landed. One of my fond memories was hiring (renting) a car in Kirkwall, the largest city. When I went to unlock it the dealer said, “It’s open. Nobody locks doors. We live on an island.” That comment has stayed with me all these years. Orkney represented what happens when population size (the islands have only about 22,000 inhabitants) doesn’t grow to the point of creating natural stresses that lead to “big city problems.”

No place is perfect, of course, but Orkney impressed us so much that we returned, with friends, a few months later. This time we took the ferry and, thankfully, they drove. We visited antiquities, met locals who were open to outsiders, and saw some of the most spectacular scenery that the British Isles has to offer. Seeing the posts of the Orkney Library and Archives on Bluesky always takes me back to a happy place. It’s one of the good things social media has to offer. And since I check it in the morning, it starts my day off well.