Comments being rare on this blog, I do read them when they come along. Recently I had a reader comment, in the form of a question (as sometimes happens): “Do Native American Indians do ‘Thanksgiving’?” Although I’m fairly certain this was intended as a rhetorical question, I was raised a literalist and couldn’t help trying to formulate an answer. Although I can make no claims to know Native American culture well (I wish I did) it led me to ponder the concept of Thanksgiving. No doubt the idea had at least informal religious beginnings. Even with the early European settlers, a religious diversity was already appearing. Still, although the Native Americans lost pretty much everything, they were still involved, at least according to the early accounts. The great spirit they thanked was not likely conceived of in the way that the god of the pilgrims was, and yet, thankfulness is a natural human response. Writers, often fully aware that their work deserves publication, frequently thank an editor for accepting it. It’s a deeply rooted biological response.

For some of us, Thanksgiving is more about having time to recuperate after non-stop work for about ten months. The standard business calendar gives the occasional long weekend, but after New Year’s the only built-in four-day weekend is Thanksgiving. It is that oasis we see in the distance as we crawl through the desert sand. Time to be together with those we love rather than those we’re paid to spend time with. To rest and be thankful.

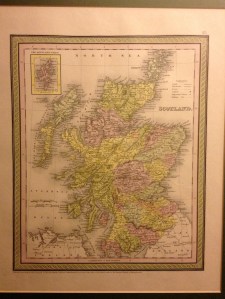

Among the highlands of Argyll, in western Scotland, is the picturesque Glen Croe. Years ago, driving with friends through the rugged scenery of boulders and heather, the little car struggled with its burden of four passengers. We stopped at a viewpoint known as “Rest and Be Thankful.” The name derives from an inscription left by soldiers building the Drover’s road in 1753, at the highest point in the climb. The Jacobite movement and the Killing Time had instilled considerable religious angst to the Scotland of the previous century and led to the calamity of Culloden less than a decade before the road was laid. These religious differences led to excessive bloodshed throughout a realm supposedly unified by the monarchy. Even though no natives protested displacement, religion led to hatred and mistrust, as it often does. Is not Rest and Be Thankful, however, for everyone, no matter their faith or ethnicity? And in case anyone is wondering, yes, this rhetorical question contains a metaphor to contemplate. Rest and be thankful.