Among the most revered traditions of the horror film is the sequel. Originally a financially driven feature, sequels have now become an expectation among fans. And although in general we prefer to appeal to our higher cultural aspirations, many horror movies do remarkably well at the box office. I’m not much of a sequel-watcher, but sometimes in my effort to understand the close connection between religion and horror, I succumb. So it was I watched The Conjuring 2. As with the formula for the initial movie, cases actually investigated by Ed and Lorraine Warren are brought together with exaggerated special effects and demonic entities. Starting out in Amityville, the demon Valak is introduced. It later appears as the source of the Enfield poltergeist.

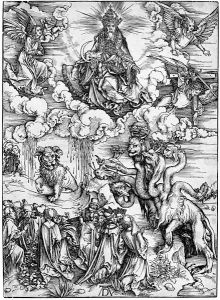

In real life controversy never strayed far from the Warrens and their investigations. Amityville and Enfield have both been implicated as hoaxes. The Hodgson girls, just like the Fox sisters in upstate New York, confessed to some faking, and, of course once that dam has been breeched, there’s no stopping the flood to follow. Nevertheless, such incidents make for good horror film fare. In the case of The Conjuring 2, bringing a named demon into the mix keeps the religious pot roiling. Ironically, the demon takes the form of a nun. This character is a complete departure from both the Amityville and Enfield of record, although demonic influences were posited for both cases. Valak appears to go back to The Lesser Key of Solomon, a grimoire familiar to watchers of the now departed Sleepy Hollow.

Even with the hoax light cast on the “based on a true story” tagline, The Conjuring is well on its way to spawning a cinematic universe. Annabelle was a spinoff, and Annabelle: Creation scored high marks this summer. The success of The Conjuring 2 has led to work on The Nun, scheduled out next year. There’s talk of a third Conjuring film as well. As religion becomes less obvious in the traditional forms of weekly worship gatherings, it crops up more in other areas of culture. Don’t get me wrong—there’s plenty of secular horror as well. What does stand out is that when religion knocks at that creaking door of horror, nobody’s especially surprised. The Conjuring 2’s climax is quickly resolved once the demon’s name is remembered. The fallen angel is banished, not so much back to Hell as to another sequel. Eternal life is, after all, a religious idea as well.