I always find undergoing anesthesia a spiritual experience. It’s too bad the the prep for things like colonoscopies is so stressful that it’s difficult to appreciate the fasting and how it changes your perceptions. This is followed by the delicious blackness of a complete loss of consciousness. If death’s like this we have nothing to fear. I’ve written about this before, but chemical sleep is not like nighttime sleep. You hear the anesthesiologist say, “You’re going to sleep now.” Then you wake up, disoriented because no time has passed. I blinked a few times, saw my wife’s coat on the wall, and thought it was a nurse. I started to say “Stop, I’m waking up!” But then I focused on my wife and wondered why they’d let her into the procedure room. “Are they done already?” I asked. Where had I been for the last hour?

Spiritual experiences are sometimes only seen in retrospect. They jar us out of ordinary time into an alternative time. It doesn’t make up for the nasty taste of prep medicine, or the unpleasantness associated with it, but emptying yourself is a spiritual practice. I need to try to remember that next time around. I know people who are afraid of anesthesia. I’ve only had it three or four times—oral surgeries, and my first such procedure as this—but there’s something mystical about it. I don’t use drugs (never have) so perhaps I’m a neophyte, but looking back on the experience I know that something extraordinary happened. Coming out of it is coming into a new world that is somehow strangely the same as the one I left.

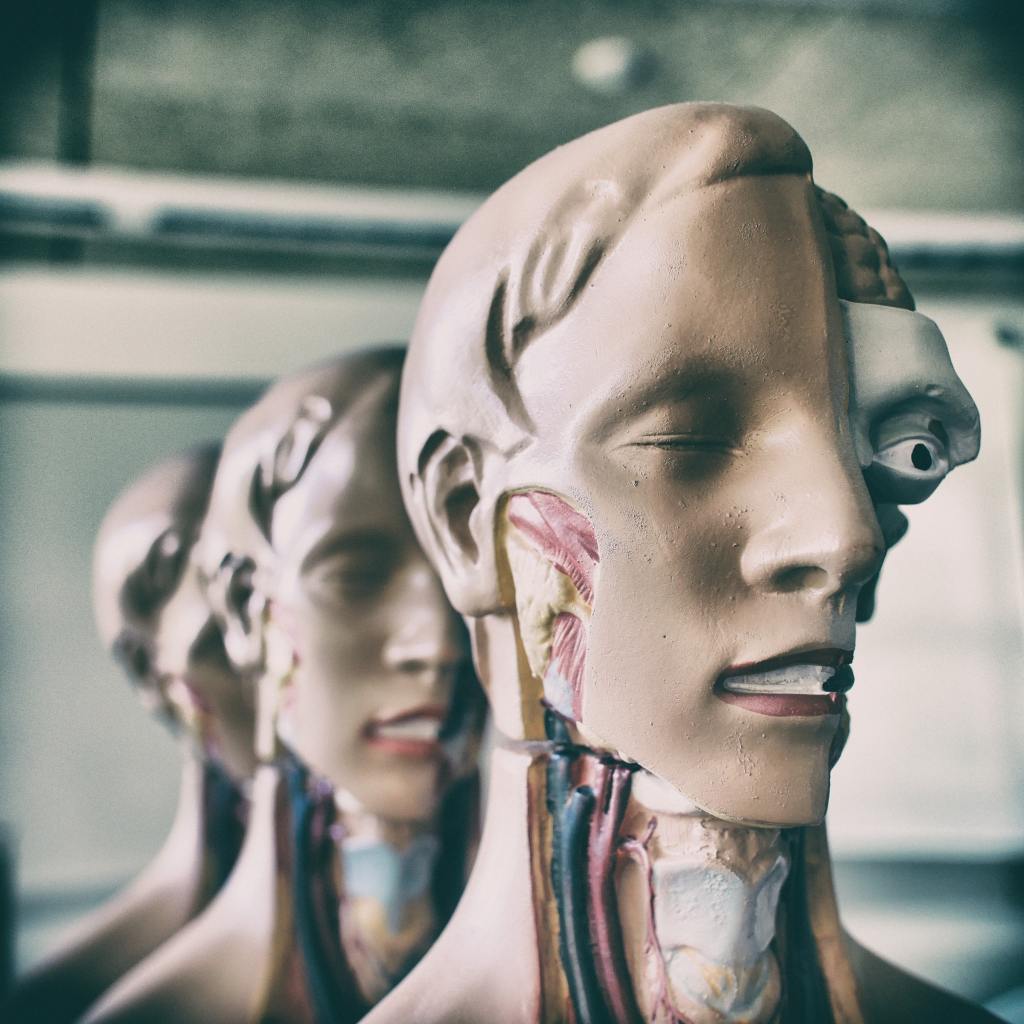

Religion has always, at least partially, been about altered states of perception. Organized religion succeeds in making it rote, but those who experience the naked phenomenon never forget it. Anesthesia is, I know, potentially dangerous. It so like a light being switched off that I’m always left in awe of it. Mystical experiences are rare, which is one of the things that makes them so valuable. I’ve had them—widely spaced—since childhood. Sometimes it’s evident in the moment, but often some reflection is necessary. I suppose few people look forward to any kind of surgical procedure, but there can be benefits beyond the physical health that we hope will result. That’s the way spiritual events often take place. Perhaps advanced practitioners (not always clergy) can bring them about intentionally, but any of us might recognize them afterwards, upon reflection.