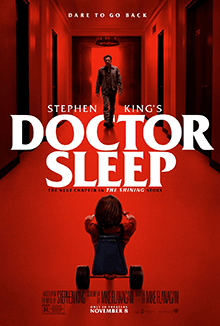

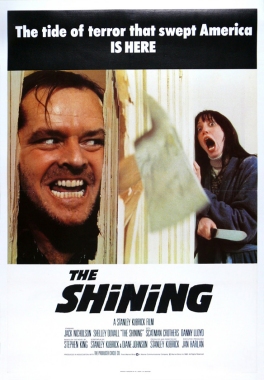

It was the choice of reading a very long Stephen King novel or watching a very long movie. The fact that Doctor Sleep was leaving Netflix soon decided the toss. I’d heard that this sequel to The Shining wasn’t bad, but not as good as the original. Stanley Kubrick’s movie is a masterpiece, so trying to follow it up requires more confidence that I would be able to muster. Still, Doctor Sleep is not bad. Danny and Wendy survive, but Dan still sees the Overlook entities coming after him. As an adult he has shut out the shine and become an alcoholic. He catches a bus to New Hampshire and meets a recovered alcoholic who befriends him. In recovery himself, he works in a hospice where he uses his shine to help those whose deaths are imminent, earning him the nickname “Doctor Sleep.”

Meanwhile, entities like those at the Overlook are killing and “eating” kids with shine, but they call it steam. Abra, a girl with very strong shine, contacts Dan because she experienced the creatures’ latest murder. The creatures’ leader, Rose, is able to project herself anywhere and she finds Abra and becomes intent on “eating” her. Dan, who realizes he has to use his shine to save her, with the help of his new friend (actually they’ve now known each other for eight years) goes to trap the entities. One of them, however, kidnaps Abra and when Dan meets her after the kidnapping he knows they have to lure Rose to the Overlook Hotel. I think I’ll stop summarizing there, but this gives you an idea of just how large a tale this is.

There are plenty of cues for those who want to be reminded of The Shining. The climax at the Overlook takes viewers back to the original location and brings back some of the characters. Overall it’s pretty well done but just what these entities, or creatures, are isn’t really explained. At a number of points the supernatural becomes almost too much. There’s no Kubrickian reserve here. The story is much more about addiction and overcoming it. Jack Torrance, after all, was an alcoholic. The movie shows this but the novel dwells on it quite a bit more. Doctor Sleep make alcoholism key to the tension Dan undergoes as an adult, even when he’s back at the Overlook, paralleling his father’s stopping in the bar. The movie threads the path between The Shining King didn’t like and his vision of what happened after that episode. Ambitious, but it does keep your attention, for a long movie.