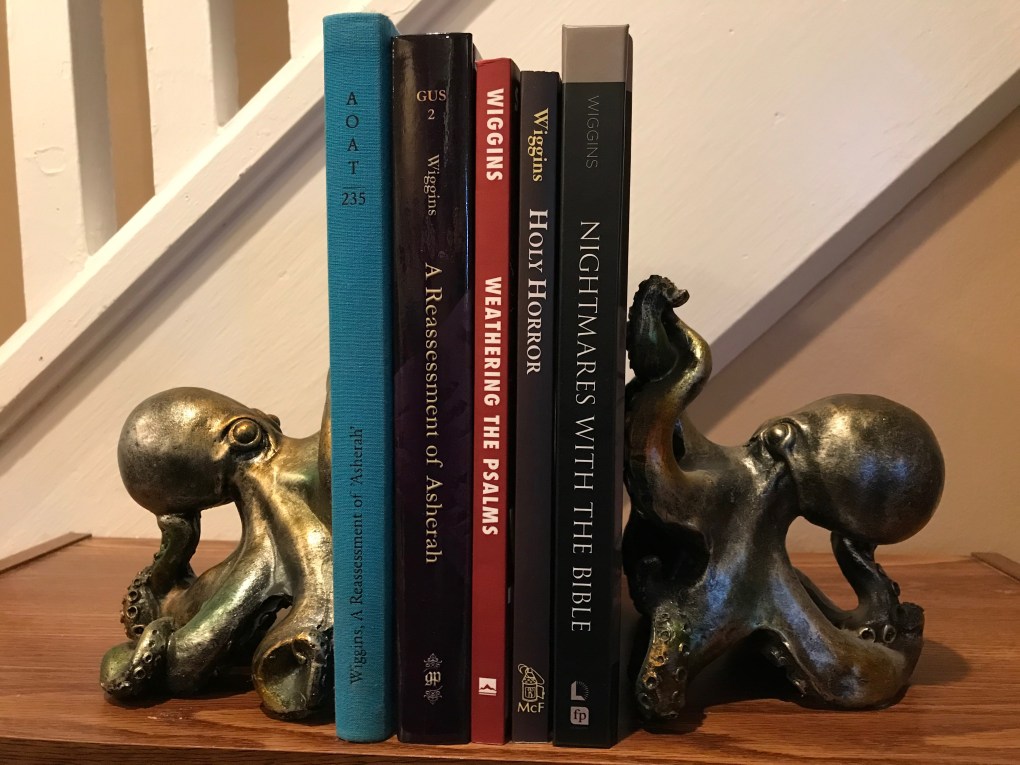

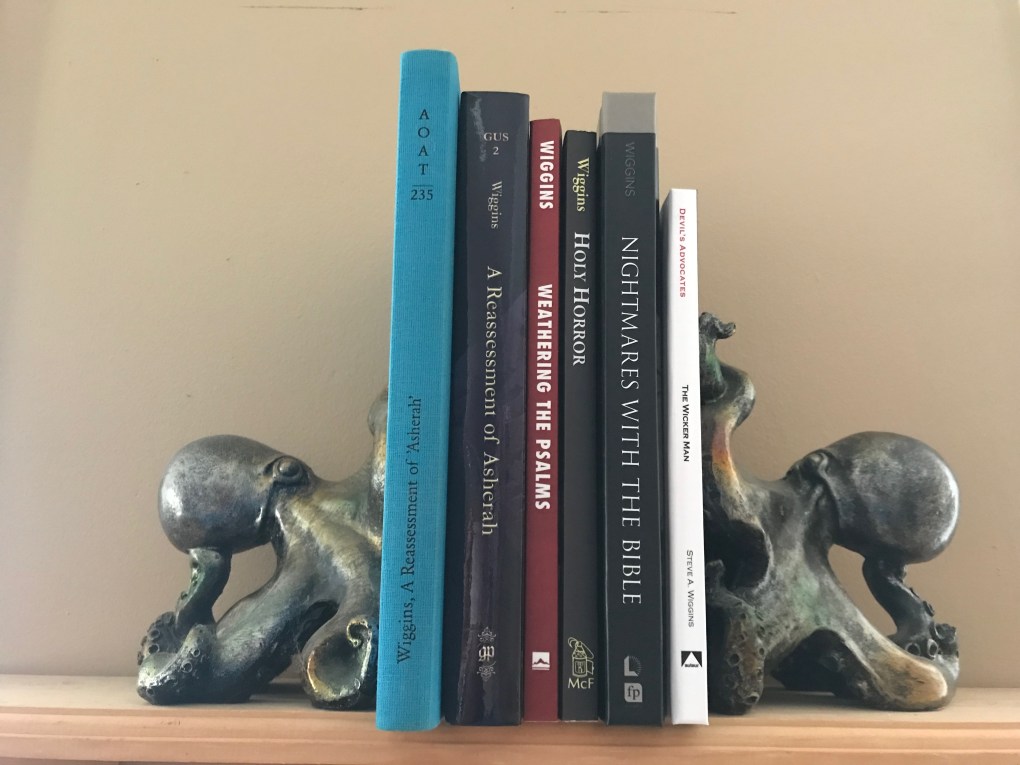

Those of us who write books have been victims of theft. One of the culprits is Meta, owner of Facebook. The Atlantic recently released a tool that allows authors to check if LibGen, a pirated book site used by Meta and others, has their work in its system. Considering that I have yet to earn enough on my writing to pay even one month’s rent/mortgage, you get a little touchy about being stolen from by corporate giants. Three of my books (A Reassessment of Asherah, Weathering the Psalms, and Nightmares with the Bible) are in LibGen’s collection. To put it plainly, they have been stolen. Now the first thing I noticed was that my McFarland books weren’t listed (Holy Horror and Sleepy Hollow as American Myth, of course, the latter is not yet published). I also know that McFarland, unlike many other publishers, proactively lets authors know when they are discussing AI use of their content, and informing us that if deals are made we will be compensated.

I dislike nearly everything about AI, but especially its hubris. Machines can’t think like biological organisms can and biological organisms that they can teach machines to “think” have another think coming. Is it mere coincidence that this kind of thing happens at the same time reading the classics, with their pointed lessons about hubris, has declined? I think not. The humanities education teaches you something you can’t get at your local tech training school—how to think. And I mean actually think. Not parrot what you see on the news or social media, but to use your brain to do the hard work of thinking. Programmers program, they don’t teach thinking.

Meanwhile, programmers have made theft easy but difficult to prosecute. Companies like Meta feel entitled to use stolen goods so their programmers can make you think your machine can think. Think about it! Have we really become this stupid as a society that we can’t see how all of this is simply the rich using their influence to steal from the poor? LibGen, and similar sites, flaunt copyright laws because they can. In general, I think knowledge should be freely shared—there’s never been a paywall for this blog, for instance. But I also know that when I sit down to write a book, and spend years doing so, I hope to be paid something for doing so. And I don’t appreciate social media companies that have enough money to buy the moon stealing from me. There’s a reason my social media use is minimal. I’d rather think.