One of the many lessons of the current pandemic has been that my appreciation of horror is not misplaced. Horror Homeroom has just published my piece “Demons or Ghosts? Hauntings in Connecticut,” available here. I’ve noticed that Horror Homeroom has had a surge of pieces since all of this began, which seems tacit evidence that horror is a coping mechanism. It’s no wonder, really. Horror often deals with “worst case scenarios” and specializes in isolating victims. Now that we’re all practicing social distancing we’ve entered into one of the main framing plots of the horror movie. Contagion isn’t an unusual trope either. My article is about neither of these, but I still maintain that watching horror is therapeutic. As with most therapy there’s good and bad varieties.

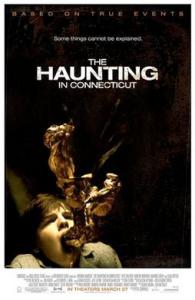

The films I write about in this instance aren’t good movies. The Haunting in Connecticut franchise misses on so many levels that it doesn’t seem bound for classic status. Yes, there are classics in the genre. When the outbreak started many people referred to The Shining as how they felt being cooped up all the time. There are those who vehemently deny that The Shining is horror, but given the association with Stephen King it seems difficult to deny. Horror doesn’t have to involve slashers or bug-eyed monsters. It isolates. It imagines worst case scenarios. All Jack Torrence needed was an inept national administration to put us all in the Overlook, one at a time.

The pandemic has slowed down the release of new movies, of course. The much anticipated A Quiet Place Part II has been pushed out to September. Sitting here in isolation I wonder if that’s long enough. Politicians with money in mind over their human constituents are chomping at the bit to get us mingling again. Exposing one another. Horror, however, knows all about aftershocks. I don’t like jump startles. I prefer my movies to built thoughtful, moody situations. Despite their many sins, the Connecticut haunting movies do that correctly. While they have other problems, they do throw us into a world where things aren’t quite right and we know it. Elaborate plots really aren’t necessary, though. The mind is pretty adept at filling in the story. Like children asking to have the same book read over and over, we know how it goes. We just like someone else to show us exactly how. Isolation should continue for some time. And horror provides a reasonable narrative to help.