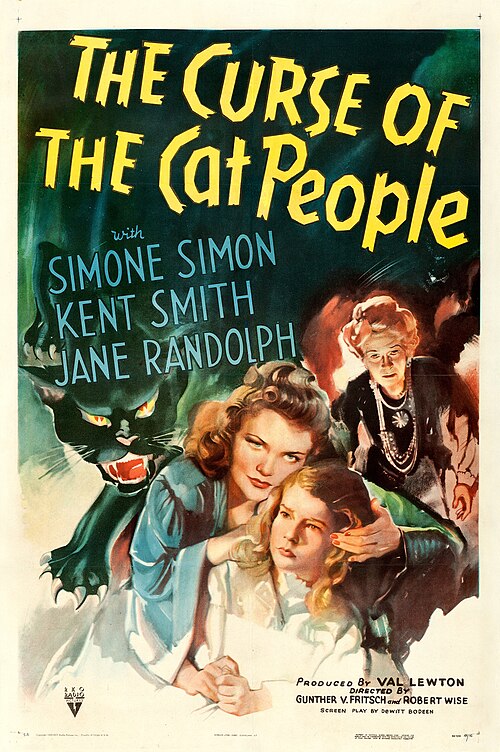

In researching Sleepy Hollow as American Myth, I watched every feature-length movie of “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” that still exists. I also watched many other productions, based, however loosely, on the Legend. I was unaware that The Curse of the Cat People should’ve been included. There is no database of all cultural references to Sleepy Hollow, and although Curse of the Cat People has many fans, nobody advertises it as related to the Legend. But it is. I happened to watch this 1944 film because I’d been thinking about Cat People. My jaw dropped when the film opened with a teacher taking her children on a walk and explaining that this was Sleepy Hollow. My book had been published just last month and I was discovering new material! The movie is a bit disjointed, apparently because studio executives wanted new material added and some of the edited pieces explaining the story were lost. Still, it is well worth seeing.

Six-year-old Amy Reed has no friends. A daydreamer who has a rich fantasy life, she frightens her father, Oliver, who had been married to Irena—one of the cat people. Oliver never believed Irena was really a cat person and is afraid his daughter is suffering under similar delusions. This is because Amy is given a ring that grants wishes by an old widow who tells her a version of the Legend of Sleepy Hollow. The wish Amy makes is for a friend and Irena, the ghost of her father’s first wife, shows up. There are no cat transformations here, but there is a great deal of psychological subtlety. Is Amy really seeing Irena or is her loneliness filling in the voids in her life—her father is distant and refuses to accept what his daughter tells him. Instead he punishes her for it.

When Amy gets lost on Christmas Eve, Irena saves her from the murderous daughter of the widow who gave her the ring. It’s clear that some of the connective tissue is missing, but the story is sincere and smart, even if only very loosely a sequel. The story of the headless horseman, pre-Disney for those of you who’ve read my book, presents the horseman as collecting unwary wanders on the bridge and compelling them to ride with him. He’s not after anybody’s head. Indeed, this is the way he’s described in Irving’s story. Just as I’ve begun collecting films for Holy Sequel, it looks like I should begin keeping a list for Sleepy Hollow as American Sequel. Curse of the Cat People will be first on the list.