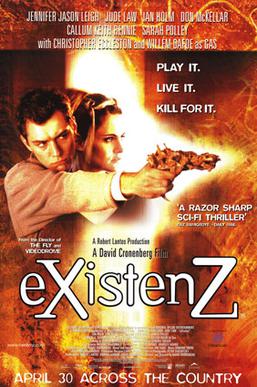

You know, I’ve referenced eXistenZ several times on this blog without really writing about it. How rude of me! Well, the fact is eXistenZ is one of my “old movies”—those that I knew from the days before I started this blog. I have watched it since 2009, but early on I didn’t review movies unless they had religious elements. Having recently referenced eXistenZ yet again, I figured it was time to look directly at it. When I first watched this movie I had no idea who David Cronenberg was. The film was recommended to me by one of my students at Nashotah House. In those days there was no streaming so I had to purchase the DVD. The movie is a science fiction horror film, primarily body horror, which is kind of Cronenberg’s shtick. It’s also about gaming and I’m not a video gamer at all. Still, I really like this film.

Perhaps presciently, Cronenberg set the movie in 2030. Computer gaming has become biological with organic ports that have to be punctured into players’ spines so they can use an “UmbiCord” to connect to the pod. Rewatching it, this seems almost too plausible. In any case, as the movie goes on it becomes less and less clear what is real and what is part of the game. Reality becomes distorted. eXistenZ came out about the same time as The Matrix (probably why my student suggested it to me). Given the very high profile of the latter film, eXistenZ never really broke out. Cronenberg seldom breaks through to the mainstream, but I know a lot of people were talking about his remake of The Fly in 1986. I even saw that one in the theater with some seminary friends. In those days I didn’t know enough about horror to know what to expect from a Cronenberg film, which may be why it had such an impact on me.

In any case, eXistenZ remains underrated. I see more recent films that appear to nod to it. The horror aspects tend to be the slimy, gooey aspects of the game world which—spoiler alert—is, diegetically, the one in which the viewer resides. There are indeed a few parallels to The Matrix, but eXistenZ has creatures and horror themes. Sci-fi horror is a sub-genre that often works. Critics tend to refer to such things by the older category of “science fiction,” but it is close kin to horror, a genre only separated out in the early 1930s. Now as AI takes over the world, it might be a good opportunity to watch eXistenZ and ponder just how far you want to let it go.