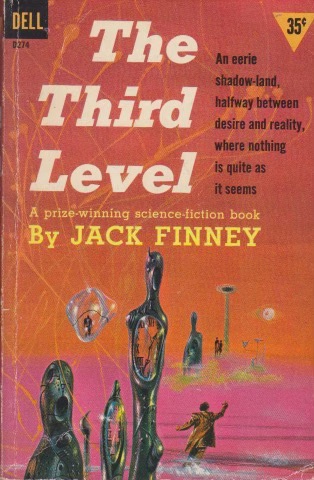

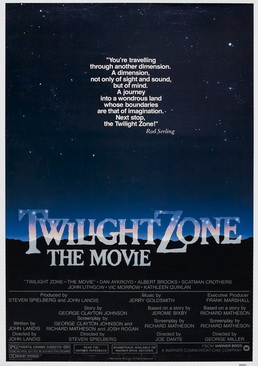

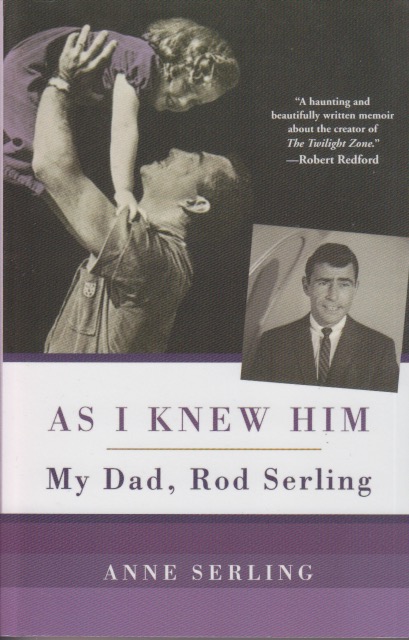

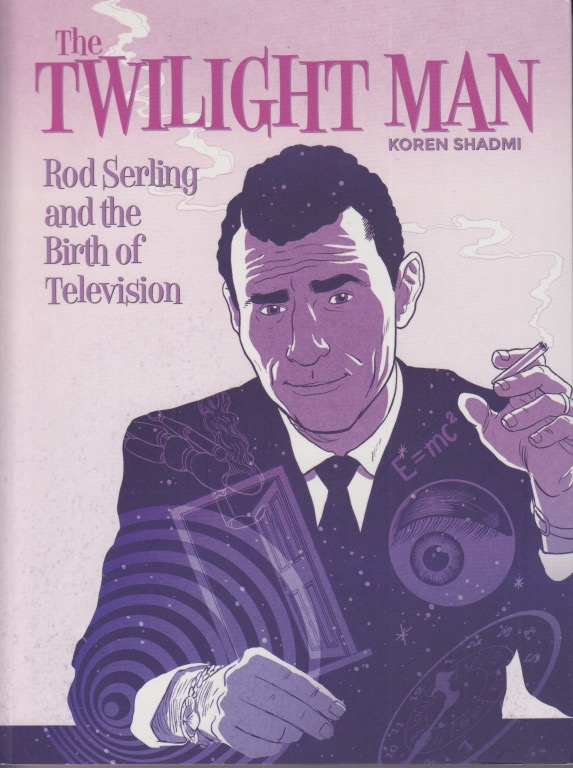

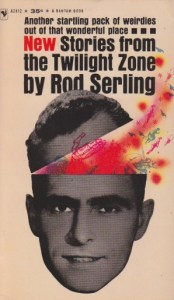

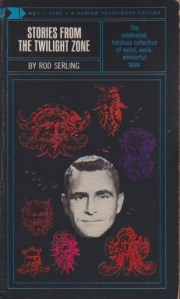

Jack Finney is probably best remembered as the person who came up with the idea for The Invasion of the Body Snatchers. His book, The Body Snatchers, was the inspiration behind the two movies based on it, as well as various knockoffs. The Third Level is a collection of short stories he wrote. I’ve been trying to introduce more short stories into my literary diet, and this one was recommended by Stephen King in Danse Macabre. Specifically, he mentioned it as being more like what The Twilight Zone should’ve been than much of what Rod Serling wrote. Now, I’m an unapologetic Rod Serling fan. This is based on memories from childhood when I watched the show and, let’s be honest here, wished he could be my father. I already had a taste for the unusual and sometimes macabre, and so I was curious what King thought might do Serling better.

The Third Level was labeled as science fiction, but sci-fi and horror share more than a boundary or two and at least four of the stories have nothing sciency about them. As a collection it’s good in the same sense as a mature reading of Ray Bradbury is good. I would’ve liked this—probably loved it—as a kid. I was reading, however, for The Twilight Zone. There are some good twist endings here, but not all the stories have them. A couple of them are pretty straightforward whimsical romances. Many of them feel very much like they were written in the forties and fifties. A couple of the stories, late in the collection, I really liked. They were a bit more Zonish than some of the others.

One of the problems in writing a brief post on a collection—and no collection is uniformly great—is that it’s difficult to give a sense of the whole. So instead I’ll just focus for a minute on the last story, “Contents of the Dead Man’s Pockets.” This one shows the power of Finney’s descriptive writing and it caused physical reactions I seldom get when reading. It involves a man climbing out on an eleventh-story ledge to reclaim an important bit of paper that blew out the window. More than once I almost had to put the book down. Fear of falling is deeply embedded in the human psyche and Finney is able to probe it for more pages than I was comfortable reading. Well done, sir. Overall, the collection is good to have read. It won’t change my mind about the Zone, however. It reached me a little too late to do that.