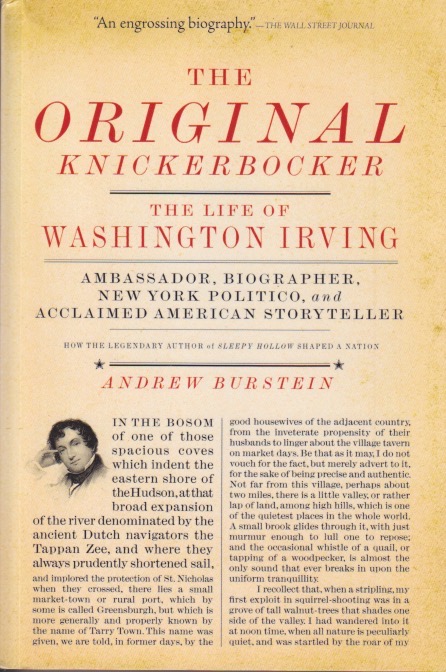

I love reading literary scholars if they write accessibly. William L. Hedges did, mostly, in Washington Irving: An American Study, 1802–1832. There were several moments in my reading when I had to pause and consider the connections he was making. This was his only book of note, but noteworthy it is. You see, as a young person I had a difficult time figuring out what I was supposed to be as an American. I read a lot about Europe and considered the various identities in the long histories there. I tended to read European literature while having a lifelong soft spot for Poe. Over time I began to read more American classics—ironically this wasn’t much part of my formal education in rural Pennsylvania. Mostly I picked things up on my own.

Hedges, nevertheless, ties many of these things together in discussing Irving’s writing. As he did so I started to realize that an American is a distinct kind of being. Now, intellectually I’ve known that since childhood. I was born and raised here, after all, as were the generations before me. Still, recognizing the guilt of taking someone else’s land, it has taken many years to appreciate the literary accomplishments of the various writers who helped shape our national identity. Hedges addresses many aspects of this through his analysis of Irving, but he’s at his best when he’s tying him together with Poe or Melville. These early American literary lights offered a view of a nation haunted by history, but also funny at the same time.

This book was published three years after I was born. Of course, I really didn’t start reading about Irving until about a decade ago. You get the sense that he wasn’t sure of himself as a writer, but like many of us he had a thin skin when it came to criticism. You see, writing is putting yourself out there for others to see. It’s only worth doing if you believe you have something to say and you want others to hear it. For many writers that means being discovered after death. Today many make livings writing acclaimed novels. They can only do so, however, because Irving and his generation suggested something new: you didn’t have to have a traditional job and just write on the side. You could, if chance cooperated, create literary works that others would purchase and support yourself that way. And then, more than a century after you’d gone, someone else would write about what you had written. Thankfully, sometimes accessibly.