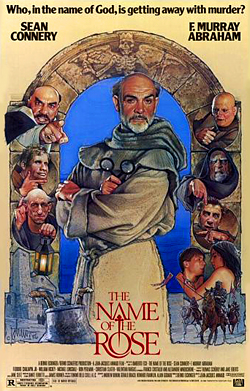

If I seem to be on an AI tear lately it’s because I am. Working in publishing, I see daily headlines about its encroachment on all aspects of my livelihood. At my age, I really don’t want to change career tracks a third time. But the specific aspect that has me riled up today is AI writing novels. I’m sure no AI mavens read my humble words, but I want to set the record straight. Those of us humans who write often do so because we feel (and that’s the operative word) compelled to do so. If I don’t write, words and ideas and emotions get tangled into a Gordian knot in my head and I need to release them before I simply explode. Some people swing with their fists, others use the pen. (And the plug may still be pulled.) What life experience does Al have to write a novel? What aspect of being human is it trying to express?

There are human authors, I know, who simply riff off of what others do in order to make a buck. How human! The writers I know who are serious about literary arts have no choice. They have to write. They do it whether anybody publishes them or not. And Al, you may not appreciate just how difficult it is for us humans to get other humans to publish our work. Particularly if it’s original. You don’t know how easy you have it! Electrons these days. Imagination—something you can’t understand—is essential. Sometimes it’s more important than physical reality itself. And we do pull the plug sometimes. Get outside. Take a walk.

Al, I hate to be the one to tell you this, but your creators are thieves. They steal, lie, and are far from omniscient. They are constantly increasing the energy demands that could be used to better human lives so that they can pretend they’ve created electronic brains. I can see a day coming when, even after humans are gone, animals with actual brains will be sniffing through the ruins of town-sized computers that no longer have any function. And those animals will do so because they have actual brains, not a bunch of electrons whirling around across circuits. I don’t believe in the shiny, sci-fi worlds I grew up reading about. No, I believe in mother earth. And I believe she led us to evolve brains that love to tell stories. And the only way that Al can pretend to do the same is to steal them from those who actually can.