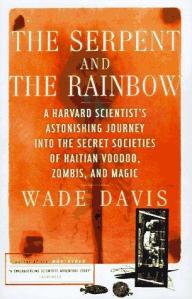

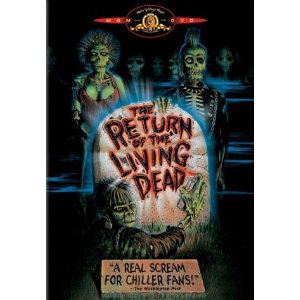

With talk of resurrection in the air, it seems natural to turn to zombies. In this internet age the monster of choice seems to change from day to day, but since the turn of the millennium zombies have been a contender for popular favorites. In a world where many of us feel zombified by our work, this is no surprise. Late capitalist power structures drain the life, leaving only the shell. In a situation where zombies appear so frequently, it is difficult to keep current. I bought Kim Paffenroth’s Gospel of the Living Dead shortly after it was published. Subtitled George Romero’s Visions of Hell on Earth, it saves itself from too my obsolescence by taking the narrative from Romero’s movies, and one remake, thus leaving room for the many other zombie movies to come and go. While it does make reference to 28 Days Later and Shaun of the Dead, most of the discussion stays pretty close to Romero, taking the reader through his quaternity of movies in the genre.

With talk of resurrection in the air, it seems natural to turn to zombies. In this internet age the monster of choice seems to change from day to day, but since the turn of the millennium zombies have been a contender for popular favorites. In a world where many of us feel zombified by our work, this is no surprise. Late capitalist power structures drain the life, leaving only the shell. In a situation where zombies appear so frequently, it is difficult to keep current. I bought Kim Paffenroth’s Gospel of the Living Dead shortly after it was published. Subtitled George Romero’s Visions of Hell on Earth, it saves itself from too my obsolescence by taking the narrative from Romero’s movies, and one remake, thus leaving room for the many other zombie movies to come and go. While it does make reference to 28 Days Later and Shaun of the Dead, most of the discussion stays pretty close to Romero, taking the reader through his quaternity of movies in the genre.

Roughly paralleling Romero’s oeuvre with Dante’s Inferno, Paffenroth treats the movies theologically. Not surprisingly, sin and ethics play a large part in his analysis. The undead, after all, are not un-spiritual. As I read along, however, I often thought how a western Pennsylvania connection gives some insight into what Romero is trying to do. Perhaps we are in danger of over-reading without the context (what biblical scholars call isogesis, but which post-modernists call simply reading). For example, some of the place names are given a theological significance in Gospel of the Living Dead that some of us who grew up in the area recognize as just another town. This always comes home to me when watching Night of the Living Dead. The posse out to hunt zombies always reminds me of people I knew in high school. After all, the first day of buck season was a local holiday.

Still, I have trouble seeing Romero agreeing with the dialogue revolving around sin. Yes, his first two movies were as much social criticism as they were horror. The Vietnam War and consumerism were true evils to be cast in parables and shown to the public. Zombies were prophets. Paffenroth suggests that zombies will never become mainstream commodities, but time has shown that even zombies can be bought out. World War Z was a Hollywood extravaganza. The Walking Dead is hardly the domain of outcasts and pariahs. Romero’s monsters were, alas, not more powerful than capitalism. Even zombies can be purchased. Zombies and vampires can indeed earn money, and resurrection itself comes with a price.