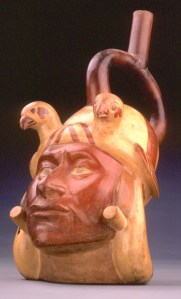

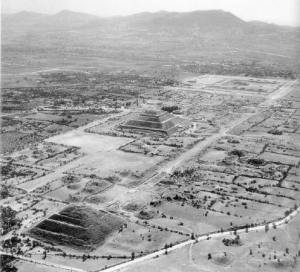

All conspiracy theories and history’s mysteries aside, there are some interesting correlations between the ancient Egyptians and the pre-European “New World.” Temples, pyramids, and large ceremonial structures are among the common features they share. Perhaps it is inevitable that where a ruling class becomes oligarchic that grand structures to their greatness will follow. Some factors transcend all times and cultures. It may be no surprise then, as MSNBC announced yesterday, that tunnels have been discovered under the ancient Mexican city of Teotihuacan. The tunnels, first noticed under the temple of Quetzacoatl, may be the entry to the tombs of the royalty, not unlike Old Kingdom Egypt. This great pre-Colombian city was already abandoned by the time the Aztecs came along. They gave the city its current name, a title that may be translated as “the place where men become gods,” according to Mark Stevenson of the Associated Press.

Not being an expert on ancient Americans, it is difficult to interpret all this information. Having read extensively on the ancient Near East, however, the parallels are unavoidable. The place where men become gods may well apply to several aspects of ancient Near Eastern thought as well. Not only the Egyptians, but also most ancient peoples attributed divinity to their kings. We have no personal statements from such rulers indicating their personal satisfaction at having been considered better than their fellow citizens, although one might speculate that captains of industry and finance share those views today. The ancients, however, seem to have taken this literally. Kings were gods. When kings died, and were conveniently no longer observable, they were among the unseen realms of the divine, continuing to influence the world from beyond the grave.

Even the Bible shares, to an extent, the idea of divine kingship. David comes pretty close to the mark in the books of Samuel, and certainly the idea had appeal in the pre-monotheistic eras of ancient Israel. The place where men become gods is, however, in the imagination. The great and powerful pharaohs do not govern the affairs of modern Egypt, nor do the shades of Assyrian and Babylonian emperors protect the war-torn realities of life in Iraq. We don’t even know who built Teotihuacan. The fate of divine kings, it seems, is to grow obscure and irrelevant to all but historians and reluctant school kids. There are those who still aspire to divine kingship. They may have lives of immense wealth and power, but if they read a little more history they would glimpse their own fate in the tombs of the divine kings.