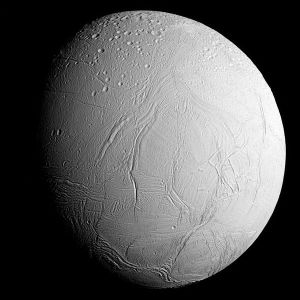

The failure of India’s Chandrayaan 2 to maintain contact, intended to make India the fourth nation to successfully conduct a lunar landing, sent me reading about the moon. I remember the first manned landing, which happened when I was six, so the idea that we could make it that far seemed less impressive than it really is, I suppose. I was fascinated by early space travel, and part of this may have been because of the moment of silence announced in school the day Apollo 13 safely returned to earth after the oxygen tank explosion that made its landing impossible. As I was reading about the many moon missions that took place before I was born, I was surprised to learn how many nations are still attempting to reach our nearest neighbor. This year alone China, Israel, and India have all attempted to land up there.

Israel’s mission called its lunar lander Beresheet. It was the first attempt to land the Bible on the moon. Beresheet is the Hebrew title of Genesis. The US missions were named Pioneer, Ranger, Surveyor, and Apollo. Ironically for the persistently religious nation, our only supernatural title was the name of a Greek deity. Israel was true to its roots with its naming convention, but there is kind of a paradox involved. In the world of the Bible the earth is the center of the universe and the moon is a quasi-living being circling about our stationary fix in this fictional view of the cosmos. That’s not to say our own views may not some day be regarded as fictional as well, but simply that we now know the view in Genesis is incorrect.

Of course, the word “genesis” can mean a purely secular beginning as well. It is a compound word that is often translated as “in the beginning.” As such, it is appropriate for the first attempt at a moon landing, or any other great venture. Still, it is instantly recognizable as the first word in the Bible, indicating a kind of strange juxtaposition where the biblical moon—which is not the same as the astronomical moon—are brought together. Unlike the book of Genesis, the moon has been reached many times by others before. The old and the new meet in this attempt to reach into space. Meanwhile our problems continue down here. Maybe that’s why we continue to attempt to reach the heavens. And in that sense, no better title applies than that of the book that somehow defies rational explanation.