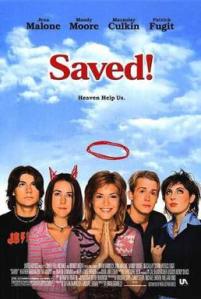

There can be no doubt that under Trump conservative Christians have been flexing their muscles. Few things corrupt so readily as political power, and evangelicalism—already an unrealistic way of looking at things—is itching to throw punches. A story on For Reading Addicts that my wife sent to me bear the title “DC Comics cancel latest comic after backlash from conservative Christians.” The piece by Rowan Jones notes that Second Coming was cancelled due to pressure from evangelicals with the cultural sensitivity of the Kouachi treatment of Charlie Hebdo. Cartoons, it seems, are a real threat to true believers in a way that reason is not. Jones notes that the comic was actually largely supportive of Christian values, but like an evangelical Brexit the reaction was taken without understanding the issue.

The anger of conservative religions—it hardly matters whether they are Christian, Muslim, or Aum Shinrikyo—often plays itself out in displays of violence. I wonder if part of this insecurity comes from the fact that the expectations of their faith don’t work out they way they’ve been led to believe they will. The myth of the blessed existence of the true believer is given the lie by life in a secular world. While the evangelicals support Trump, 45’s tax plan takes money from their pockets and hand it to the ultra-wealthy. This raises no objections, but a cartoon showing Jesus helping the poor?—now that’s offensive! And still no second coming takes place. It’s difficult to retain a fantasy view in the face of cold reality.

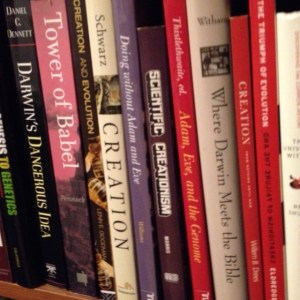

Religious beliefs are a deeply personal matter. It is a dicey business to try to get someone to change their outlook when they’ve been convinced that the consequences are eternal. Although vaguely aware of other religions all along, Christianity in the “new world” was taken quite by storm at the 1893 World’s Parliament of Religions in Chicago. Suddenly it was clear that other moral, decent religions had developed similar ethics to what had largely been supposed to have been Christian innovations. It’s difficult to feel superior when others in the same room seem just as intent on improving the lot of humankind as you do. Even when a particular religion holds all the political power of a nation it’s overly sensitive to cartoons. This is a curious situation indeed. I’m not a comic book reader—I don’t even have time for internet articles unless someone sends them to me with the suggestion that they’re worth my time. And I, for one, think a little more humor might just make the world a better place. Either that or we need a hero.