I’ve always been interested in the sky. At times it feels like I’m in love with it. Having attended a Sputnik-era high school—a rural high school with an actual planetarium!—I took the offered astronomy course. Buoyed up by this, I also enrolled in a college astronomy class only to discover that that career track involved far too much math for my humble abilities. Still, I learned a lot about the nighttime sky. I’ve also been a lifelong reader of lay science. I very much appreciate scientists who write so that nonspecialists can understand them. So it was that I was glad to see a New York Times letter by Adam Frank and Marcelo Gleiser titled “The Story of Our Universe May Be Starting to Unravel.” I’ve mentioned Gleiser here before because I’ve read a couple of his wonderful books. But this article was mind-expanding.

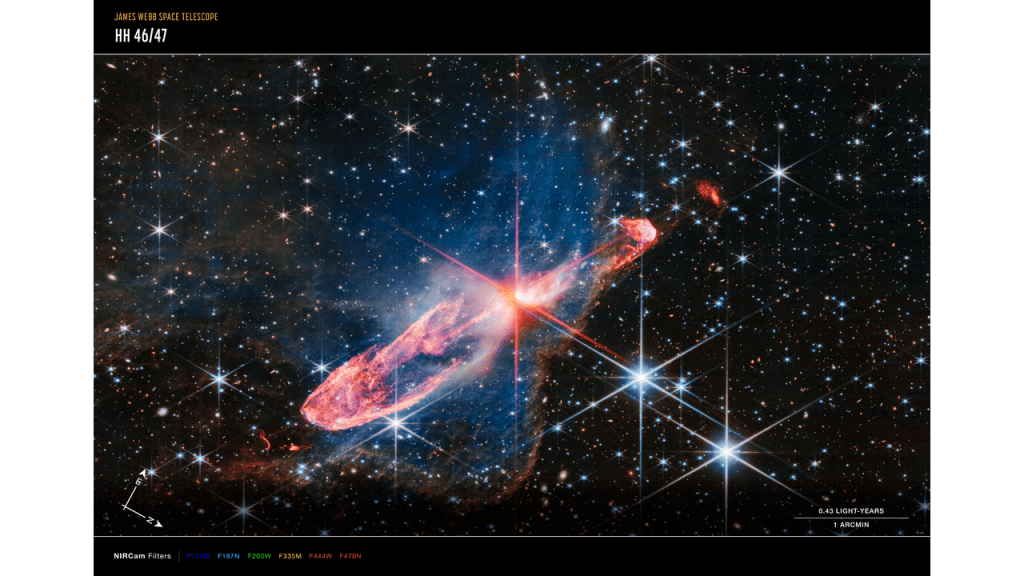

Frank and Gleiser suggest that the Big Bang Theory may, eventually, need to be replaced. They point out that small inconsistencies have crept into it over the years (keep in mind that it was really only “confirmed” within my lifetime, back in the sixties). Most of these have been patched up with quilt-work astrophysics, but the James Webb Space Telescope is making some of those past patches strain a bit at the seams. Fully formed galaxies are being spied too far back in time (for stargazing is looking into the deep past) for the standard model. They shouldn’t be there, but they are. The letter interestingly raises the point that the scientific study of quantum physics, as well as that of consciousness, also strain the standard models. Perhaps it’s time for a rethinking of reality?

Isn’t this breathtakingly exciting? To be alive when a major leap of understanding the universe we call home may be discovered? The authors point out that cosmology and philosophy often have to interact. Our understanding of the universe is a human understanding, not sacred writ. The scientific method is built to be falsifiable. If it’s not, it’s not science. (This often separates it from some religions which declare themselves unfalsifiable, and therefore likely wrong.) New scientific discoveries are made daily, of course, but new paradigms only tend to come on the scale of lifetimes, or several generations. We don’t see them all the time. I guess it’s heartening to see that the system works. When science becomes orthodoxy, we run into similar problems that we encounter with religions. A bit of humility and a ship-load of wonder can go a long, long way.