After reading many popular books, coming to a scholarly tome can be a shock to the system. This is especially the case when said academic volume contains lots of information (not all do, believe me!). David Brakke’s Demons and the Making of the Monk: Spiritual Combat in Early Christianity has been on my reading list for quite some time. One of the perils of being a renegade academic is that you have no university library at hand and I’m not sure I want to reveal this side of myself to the local public librarian yet. In any case, it would be difficult to summarize all that Brakke covers in this insightful treatment. One of the elements that struck this reader, however, is the protean nature of the demons with which the eponymous monks wrestled.

After reading many popular books, coming to a scholarly tome can be a shock to the system. This is especially the case when said academic volume contains lots of information (not all do, believe me!). David Brakke’s Demons and the Making of the Monk: Spiritual Combat in Early Christianity has been on my reading list for quite some time. One of the perils of being a renegade academic is that you have no university library at hand and I’m not sure I want to reveal this side of myself to the local public librarian yet. In any case, it would be difficult to summarize all that Brakke covers in this insightful treatment. One of the elements that struck this reader, however, is the protean nature of the demons with which the eponymous monks wrestled.

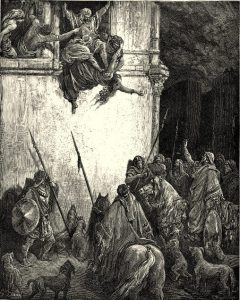

Keep in mind that although demons appear throughout the Bible in various forms there is no single definition of what they are. They appear to be spiritual monsters, in short. Some passages seem to suggest they are fallen angels. Others that they are foreign (primarily pre-Christian) gods. Later ideas add the possibility that they are children of the Watchers, or even, as Brakke explains, evil thoughts. The desert monks didn’t dwell on trying to discern their origin myth—they were out there to purify their souls, not to do academic research. The Hebrew Bible does suggest that demons were creatures of the desert. As monasticism began, appropriately in Egypt, one natural resource found in abundance was wilderness real estate. The mortgage, however, was a constant struggle with demons.

Many of these demons developed into the seven deadly sins. Not surprisingly, men living alone in the desert found themselves the victims of sexual temptation. This led to, in some cases, the demonizing of women. We’d call this classic blaming the victim, but this is theology, not common sense. Anything that stood between a monk and his (sometimes her) direct experience of God could, in some sense, be considered demonic. Brakke presents a description of several of these early desert-dwellers and their warfare with their demons. Much of their characterization of evil would be considered racist and sexist today. Brakke does make the point that during the Roman Empire—the period of the earliest monks—race wasn’t perceived the same way that it is in modern times. Nevertheless, some of this book can make the reader uncomfortable, and not just because of demons. Or, perhaps, that’s what they really are after all.