Difficult to believe as it may be, some of the biggest superstars in America’s history have been clergy. The case has been firmly made that George Whitefield, the evangelist, was the first to hold “rock star” status in these United States. He drew stadium-sized crowds before there were stadiums and was, perhaps, the most famous man in the country. Fast forward a number of years and we find a name that may not ring so many bells today. Aimee Semple McPherson, however, was more famous than Hollywood actors and most political figures of her day. The founder of the Foursquare Gospel church was, in the roaring ‘20s, one of the most recognizable names in America. It may not count for much, but even in rural Pennsylvania we learned about her in American History class in high school four decades after her time.

Difficult to believe as it may be, some of the biggest superstars in America’s history have been clergy. The case has been firmly made that George Whitefield, the evangelist, was the first to hold “rock star” status in these United States. He drew stadium-sized crowds before there were stadiums and was, perhaps, the most famous man in the country. Fast forward a number of years and we find a name that may not ring so many bells today. Aimee Semple McPherson, however, was more famous than Hollywood actors and most political figures of her day. The founder of the Foursquare Gospel church was, in the roaring ‘20s, one of the most recognizable names in America. It may not count for much, but even in rural Pennsylvania we learned about her in American History class in high school four decades after her time.

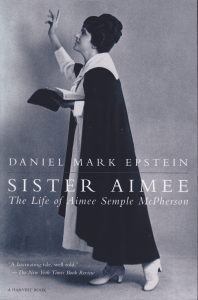

I read quite a lot about American religion, and Aimee Semple McPherson frequently comes up. I knew little about her, however, until reading Daniel Mark Epstein’s Sister Aimee: The Life of Aimee Semple McPherson. While it has its faults as a biography, it does convey a fair image of who this fascinating woman was. An evangelist when few women preachers existed, she was creative, crowd pleasing, and remarkably broad-minded for a Fundamentalist. Her personal life was full of drama—three marriages and at least one kidnapping episode—wealth, and want. She trusted Jesus implicitly and often suffered alone in silence. Secretly she befriended Charlie Chaplin, a man drawn to her stage presence but not her religion. It’s difficult not to like this woman who insisted on doing things her own way, and who ended up alienating her family (apart from her son) by doing so.

There can be no doubt that Aimee Semple McPherson believed what she said she did. Although she didn’t approve of theater she brought theatrics into church via her famous “illustrated sermons.” She pioneered radio evangelism, which subsequently grew into a hackneyed soapbox for lesser thinkers. She was a faith healer, a world traveler, and a woman who genuinely cared for the poor. Epstein’s book tells the story with heart and a touch of hagiography, but it is an entryway into one of the lives that shaped Jazz Age America, even if it is now largely forgotten behind flappers and Fitzgerald. It’s hard to believe that some of the most famous people in American history were religious leaders of their time, especially when we see what’s on offer in that arena today.